“When she said she was 13, a man came and said, ‘Y’all free. Y’all free,'” said Willie Mae Coleman.

DALLAS — There is pride in knowing who you are as a person.

Willie Mae Coleman has 89 years worth of stories to tell.

“We were poor. Our parents were very very poor. Poor as dirt,” said Ms. Coleman. “But the music. People start playing music, they forget all of that child. We’d all be out there in the neighborhood dancing.”

Ms. Coleman grew up in South Dallas. Many refer to her as the unofficial mayor of South Dallas.

Her work in the community and with various leaders backs that up too. Her home has dozens of plaques, trophies and awards commending her work.

She has created memories just like the ones shared with her family.

“His mother always dressed him up,” said Ms. Coleman as she showed pictures of relatives.

“That’s my mom,” said Ms. Coleman. “Eulah Mae Shaw, that was her maiden name.”

Her grandmother was Safronia Shaw. Her maiden name was Townsend. It is the last name belonging to Mr. Townsend who owned the Louisiana farm where her family had little option but to work and live there.

“He owned my grandmother and them,” said Ms. Coleman. “When she said she was 13, a man came and said, ‘Y’all free. Y’all free.’ My grandmother said, ‘Free?’ He said, ‘Yeah, the Massa can’t tell you what to do now because y’all, we’re free.’”

“Mr. Townsend said you are going to work. You are my negroes. You’re going to work. They said no and they fought,” said Ms. Coleman. “My grandmother said her daddy gave everybody shotgun and said, ‘We finished this war out.’ They’d shoot up there at them. They’d shoot down at them. And one of the bullets hit her in her arm. By the grace of God, she had fat arms. It went through the fat and came out on the other side.”

It is amazing the stories she continues to pass down, but it is daunting the stories she simply does not know.

“What my grandmother’s real name was, I don’t know. I’d like to, really liked to know, but her mother died young,” said Ms. Coleman.

It is a disheartening reality for most descendants from Africa.

“The census is very important because it tells you, one, whether they could read or write, how much property they owned,” said Marvin Dulaney, Dallas’ African American Museum Deputy Director and COO. He is also the National President of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH).

“And it just sort of gives you a capsule, or a snapshot of how they were living and what was happening to them at, at in each decade,” said Dulaney.

When researching Black families, most historians hit what they call the 1870 brick wall.

“Prior to 1870, 90% of African Americans were enslaved. In 1860, they were going to be listed on a slave schedule. A lot of times, it’ll just have their first names,” said Dulaney. “They just sort of listed them, you know, by, what they were doing, laborer, a blacksmith, and so on. They didn’t even give their first names in 1840, or 1850. They did in 1860. They gave you a first name for the people. And again, it was on the slave schedule.”

That is why American Ancestors started the 10 Million Names Project.

“We are seeking to recover and restore the names of the estimated 10 million men, women and children who were enslaved,” said Cynthia Evans, 10 Million Names Research Director and a genealogist.

They are working to tear down that 1870 wall.

“It’s important to uncover this information because we know that family history typically gives people a great sense of worth,” said Evans.

For the past month, Evans has been coming to the State Archives in Austin to research Ms. Coleman’s family history. After weeks of researching, she came to Dallas to meet Ms. Coleman and her cousin, Gina Walker Jackson, to show them what she found.

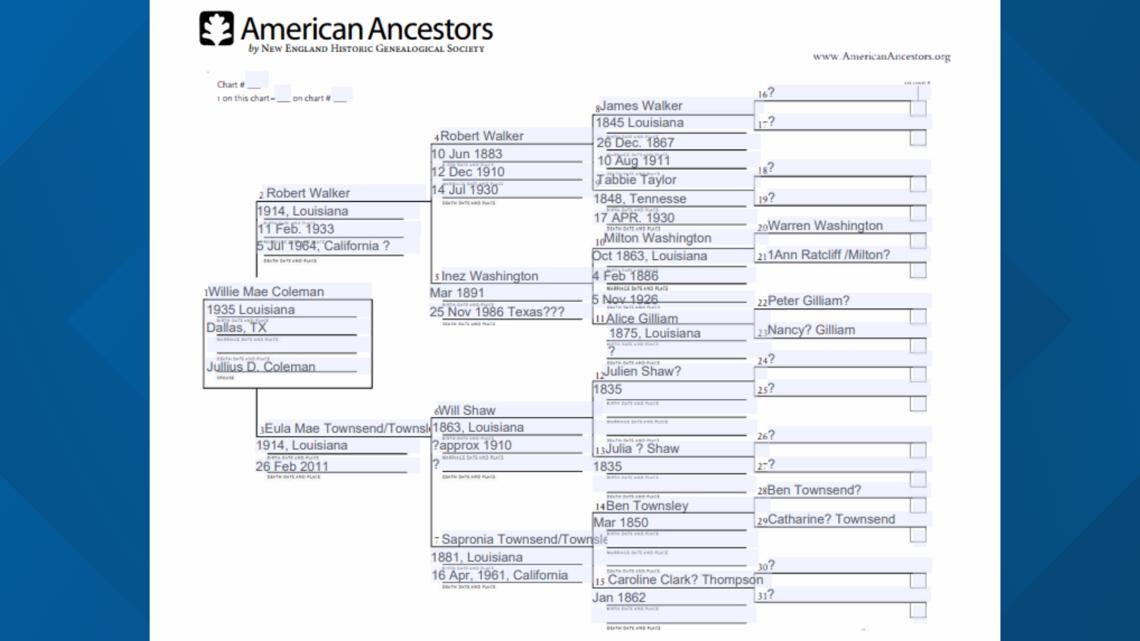

“Well, I have a five-generation family chart for you, and so I have the majority of it filled out,” said Evans. “It goes father’s family and mother’s family.”

“Okay. There’s my dad’s family,” said Ms. Coleman.

“Tabbie married James,” said Evans.

Tabbie Taylor is Ms. Coleman’s great-great-grandmother on her father’s side. She was born in 1848.

“Aunt Tabbie. And Tabbie they used to talk about,” said Walker Jackson.

“When we went to Louisiana to the family reunion and was out there working in the graveyard. She was out there,” said Ms. Coleman.

“And so, then the people at the very edge I wasn’t able to find, the parents for James Walker. I mean, he was born in 1845. So, we’re talking about pretty early,” said Evans.

“1845,” said Ms. Coleman.

Little information was passed down through word of mouth on Ms. Coleman’s father’s side of the family; however, her grandmother on her mother’s side, Safronia, shared the family history.

“So, there is an interesting thing about Safronia’s family. She is a Townsend, but I found, a census document with her name. It looks like they may have gone back and forth between Townsley and Townsend,” said Evans. “Slavery really obscured a lot of that information. The fact that people were not allowed to learn how to read and write.”

Slavery was abolished in 1865, but freedom for many was not the freedom they had hoped for.

“You’ve talked about the story of when Safronia finds out that she is free. When I did research, what I found was Safronia was born around 1880’s,” said Evans. “It tells you about what they experienced because more than likely, she’s talking about sharecropping.”

Sharecropping is a system in which a person rents a portion of land and pays the owner with a share of the crop.

“As African Americans, sharecropping was experienced almost like slavery. You have some of the same restrictions. The law enforced that. But that’s still it’s an amazing story. Anytime you get a story from family to help you fill in the gaps and give you a glimpse of what suffering is, life was like, you know, yeah. When you talk about the joy of them finding that they were free,” said Evans.

“She said it was an amazing day for her. Oh, they danced around and celebrated in the dirt and kicked up their heels. They were free. I know she did it. Oh. It’s amazing to think back to how that could be. Now I think in some places, almost. Almost,” said Ms. Coleman.

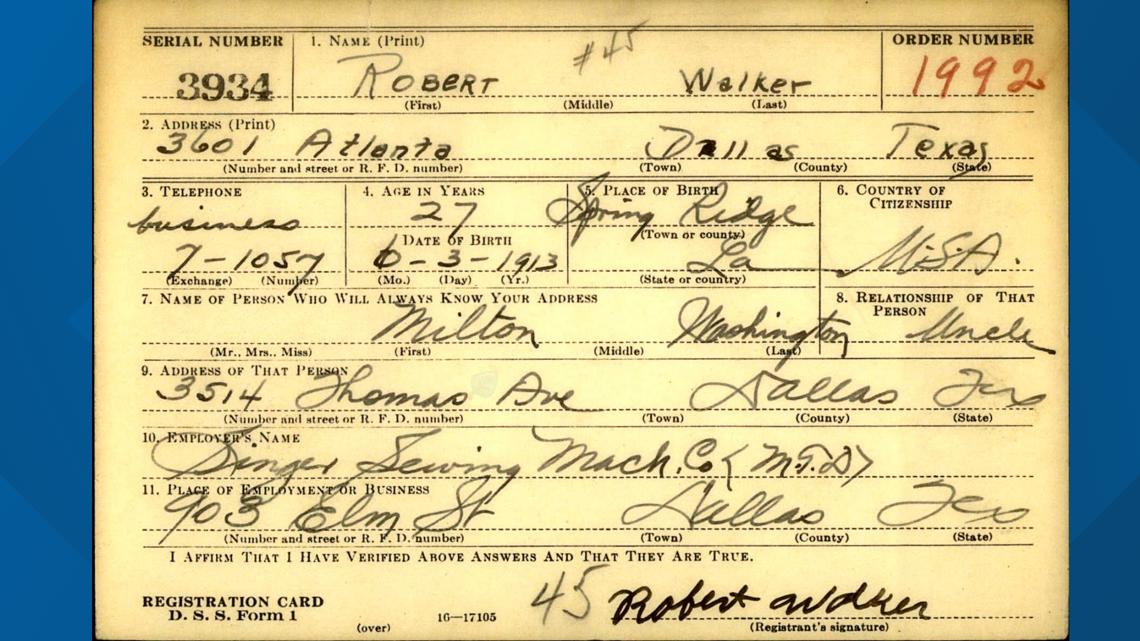

While imagining the joy her grandmother must have felt, she also felt a joy of her own. Evans surprised her with her father’s WWII registration card.

Ms. Coleman’s father, Robert Walker, was a man who defended this country’s freedom but had to move his family from Louisiana to Dallas and, himself, to California in search of a freedom of his own.

“I said, ‘It’s all over, all over the world, Daddy.’ I was nothing but 10 then, and I said, ‘It is everywhere,’” said Ms. Coleman.

Her dad moved to California when she was around 10 years old.

“You never free as you want, like you think you just can live and kind of go where you want to go, but you just don’t go nowhere. You still go among your people even though you’re free,” said Ms. Coleman.

Seeing that WWII card brought chills to Ms. Coleman as she verified every detail written on it.

“To see their eyes light up, to see them connect with history maybe in a little bit different way, seeing it in the document and then talking about what they know about their family. It’s a beautiful feeling,” said Evans.

“I’m rejoicing. And I’m so happy. I’m so happy because to know that somebody that this is where we come from. I just want to know more and more and more,” said Ms. Coleman.

The 10 Million Names Project aims to uncover the names of millions of African descendants prior to 1870. They are looking for individuals and families to get involved.

If anyone would like to participate or discover their family history, click here. Visit the 10 Million Names Project website to find out more about the project and how to contribute to the rich history.