On Sept. 9, 1994, space shuttle Discovery took to the skies on its 19th trip into space. During their 11-day mission, the STS-64 crew of Commander Richard “Dick” N. Richards, Pilot L. Blaine Hammond, and Mission Specialists Jerry M. Linenger, Susan J. Helms, Carl J. Meade, and Mark C. Lee demonstrated many of the space shuttle’s capabilities. They used a laser instrument to observe the Earth’s atmosphere, deployed and retrieved a science satellite, and used the shuttle’s robotic arm for a variety of tasks, including studying the orbiter itself. During a spacewalk, Lee and Meade tested a new device to rescue astronauts who found themselves detached from the vehicle. Astronauts today use the device routinely for spacewalks from the International Space Station.

Left: The STS-64 crew patch. Middle: Official photo of the STS-64 crew of L. Blaine Hammond, front row left, Richard “Dick” N. Richards, and Susan J. Helms; Mark C. Lee, back row left, Jerry M. Linenger, and Carl J. Meade. Right: The patch for the Lidar In-space Technology Experiment.

Left: The STS-64 crew patch. Middle: Official photo of the STS-64 crew of L. Blaine Hammond, front row left, Richard “Dick” N. Richards, and Susan J. Helms; Mark C. Lee, back row left, Jerry M. Linenger, and Carl J. Meade. Right: The patch for the Lidar In-space Technology Experiment.

In November 1993, NASA announced the five-person all-veteran STS-64 crew. Richards, selected as an astronaut in 1980, had made three previous spaceflights, STS-28, STS-41, and STS-50. Lee, a member of the astronaut class of 1984, had two flights to his credit, STS-30 and STS-47, as did Meade, selected in 1985 and a veteran of STS-38 and STS-50. Each making their second trip into space, Hammond, selected in 1984 had flown on STS-39, and Helms, from the class of 1990 had flown on STS-54. In February 1994, NASA added first time space flyer Linenger to the crew, partly to make him eligible for a flight to Mir. He holds the distinction as the first member of his astronaut class of 1992 to fly in space.

Left: Workers tow Discovery from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: Space shuttle Discovery arrives at Launch Pad 39B, left, with space shuttle Endeavour still on Launch Pad 39A. Right: The STS-64 crew exits crew quarters at KSC on their way to the launch.

Left: Workers tow Discovery from the Orbiter Processing Facility to the Vehicle Assembly Building at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida. Middle: Space shuttle Discovery arrives at Launch Pad 39B, left, with space shuttle Endeavour still on Launch Pad 39A. Right: The STS-64 crew exits crew quarters at KSC on their way to the launch.

Discovery returned to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center (KSC) in Florida following its previous flight, the STS-60 mission, in February 1994. Workers in KSC’s Orbiter Processing Facility (OPF) removed the previous payload and began to service the orbiter. On May 26, workers moved Discovery into the Vehicle Assembly Building for temporary storage to make room in the OPF for Atlantis, just returned from Palmdale, California, where it underwent modifications to enable extended duration flights and dockings with space stations. Discovery returned to the OPF for payload installation in July, and rolled back to the VAB on Aug. 11 for mating with its external tank and solid rocket boosters. Discovery rolled out to Launch Pad 39B on Aug. 19, with its sister ship Endeavour still on Launch Pad 39A following the previous day’s launch abort. The six-person crew traveled to KSC to participate in the Terminal Countdown Demonstration Test, essentially a dress rehearsal for the launch countdown, on Aug. 24.

Liftoff of Discovery on the STS-64 mission.

Liftoff of Discovery on the STS-64 mission.

On Sept. 9, 1994, after a more than two-hour delay caused by inclement weather, Discovery thundered into the sky to begin the STS-64 mission. Eight and a half minutes later, the orbiter and its crew reached space, and with a firing of the shuttle’s Orbiter Maneuvering System (OMS) engines they entered a 160-mile orbit inclined 57 degrees to the equator, ideal for Earth and atmospheric observations. The crew opened the payload bay doors, deploying the shuttle’s radiators, and removed their bulky launch and entry suits, stowing them for the remainder of the flight. They began to convert their vehicle into a science platform.

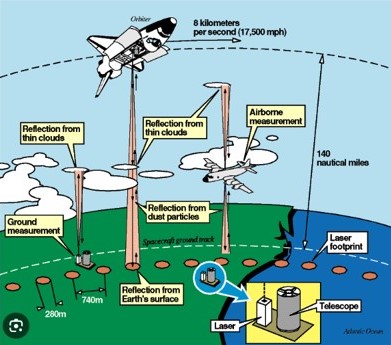

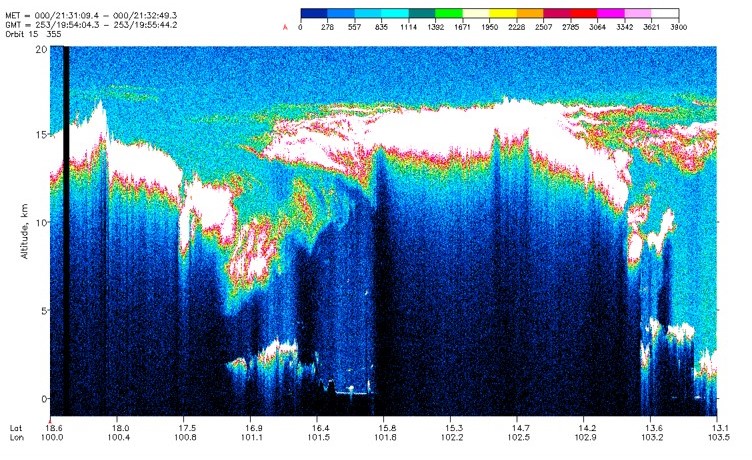

Left: LIDAR (light detection and ranging) In-space Technology Experiment (LITE) telescope in Discovery’s payload bay. Middle: Schematic of LITE data acquisition. Right: Image created from LITE data of clouds over southeast Asia.

Left: LIDAR (light detection and ranging) In-space Technology Experiment (LITE) telescope in Discovery’s payload bay. Middle: Schematic of LITE data acquisition. Right: Image created from LITE data of clouds over southeast Asia.

One of the primary payloads on STS-64, the LIDAR (light detection and ranging) In-space Technology Experiment (LITE), mounted in Discovery’s forward payload bay, made the first use of a laser to study Earth’s atmosphere, cloud cover, and airborne dust from space. Lee, with help from Richards and Meade, activated LITE, built at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, on the flight’s first day. The experiment operated for 53 hours during the mission, gathering 43 hours of high-rate data shared with 65 groups in 20 countries.

Left: View of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System, or robotic arm, holding the 33-foot long Shuttle Plume Impingement Flight Experiment (SPIFEX). Middle: Closeup view of SPIFEX. Right: A video camera view of Discovery from SPIFEX.

Left: View of the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System, or robotic arm, holding the 33-foot long Shuttle Plume Impingement Flight Experiment (SPIFEX). Middle: Closeup view of SPIFEX. Right: A video camera view of Discovery from SPIFEX.

The Shuttle Plume Impingement Flight Experiment (SPIFEX), built at NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Houston, consisted of a package of instruments positioned on the end of a 33-foot boom, to characterize the behavior of the shuttle’s Reaction Control System (RCS) thrusters. On the flight’s second day, Helms used the shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System (RMS), or robotic arm, to pick up SPIFEX. Over the course of the mission, she, Lee, and Hammond took turns operating the arm to obtain 100 test points during various thruster firings. A video camera on SPIFEX returned images of Discovery from several unusual angles.

Left: Astronaut Susan J. Helms lifts the Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy-201 (SPARTAN-201) out of Discovery’s payload bay prior to its release. Middle: Discovery approaches SPARTAN during the rendezvous. Right: Astronaut Susan J. Helms operating the Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System prepares to grapple SPARTAN.

Left: Astronaut Susan J. Helms lifts the Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy-201 (SPARTAN-201) out of Discovery’s payload bay prior to its release. Middle: Discovery approaches SPARTAN during the rendezvous. Right: Astronaut Susan J. Helms operating the Shuttle’s Remote Manipulator System prepares to grapple SPARTAN.

On the mission’s fifth day, Helms used the RMS to lift the Shuttle Pointed Autonomous Research Tool for Astronomy-201 (SPARTAN-201) satellite out of the payload bay and released it. Two and a half minutes later, SPARTAN activated itself, and Richards maneuvered Discovery away from the satellite so it could begin its science mission. On flight day seven, Discovery began its rendezvous with SPARTAN, and Hammond flew the shuttle close enough for Helms to grapple it with the arm and place it back in the payload bay. During its two-day free flight, SPARTAN’s two telescopes studied the acceleration and velocity of the solar wind and measured aspects of the Sun’s corona or outer atmosphere.

Left: Patch for the Simplified Aid for EVA (Extravehicular Activity) Rescue (SAFER). Middle: Astronauts Mark C. Lee, left, and Carl J. Meade during the 15-minute prebreathe prior to their spacewalk. Right: Lee, left, tests the SAFER while Meade works on other tasks in the payload bay.

Left: Patch for the Simplified Aid for EVA (Extravehicular Activity) Rescue (SAFER). Middle: Astronauts Mark C. Lee, left, and Carl J. Meade during the 15-minute prebreathe prior to their spacewalk. Right: Lee, left, tests the SAFER while Meade works on other tasks in the payload bay.

On flight day seven, in preparation for the following day’s spacewalk, the astronauts lowered the pressure in the shuttle from 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi) to 10.2 psi to reduce the likelihood of the spacewalkers, Lee and Meade, from developing decompression sickness, also known as the bends. As an added measure, the two spent 15 minutes breathing pure oxygen before donning their spacesuits and exiting the shuttle’s airlock.

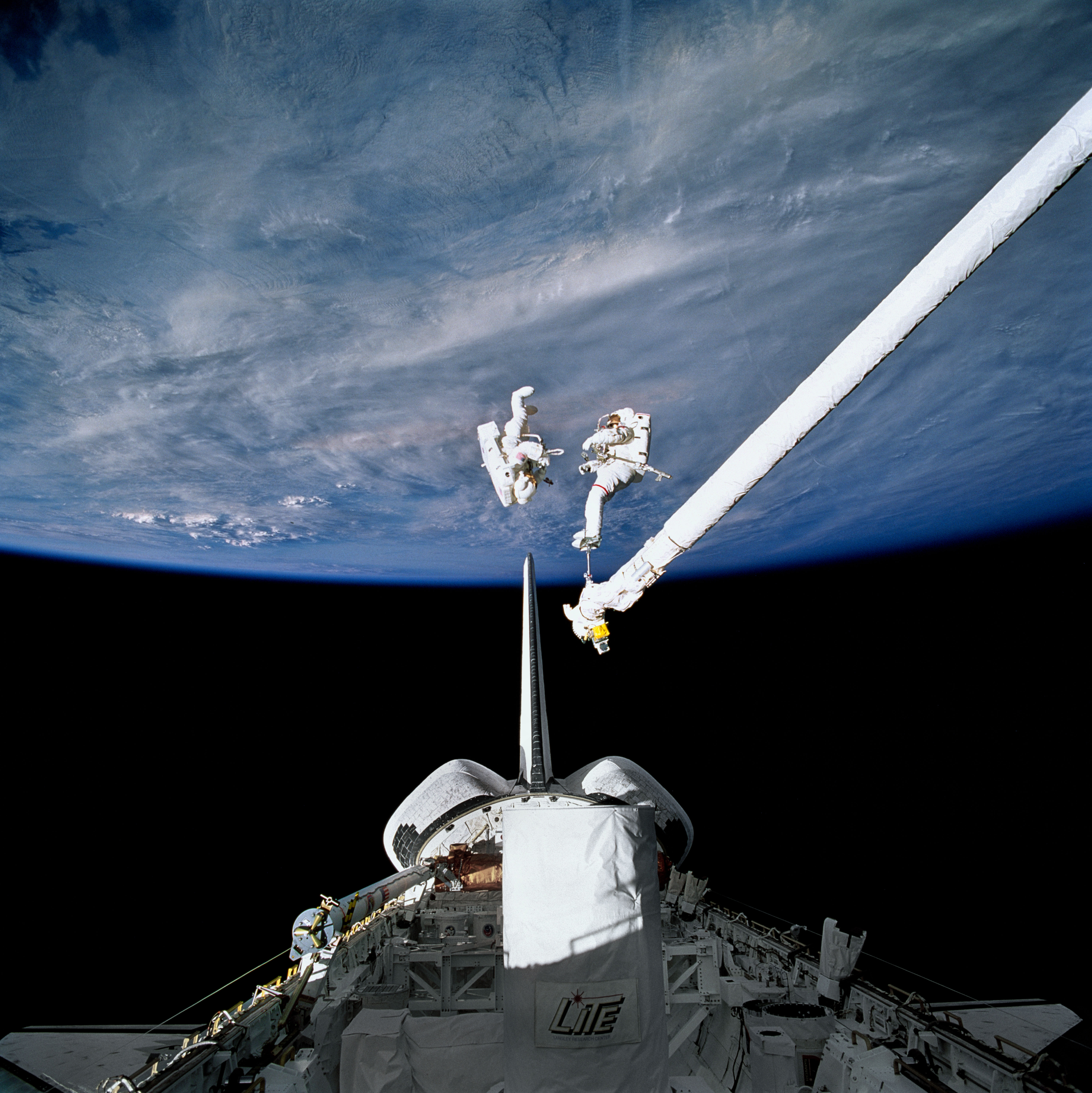

Left: Astronaut Mark C. Lee tests the Simplified Aid for EVA (Extravehicular Activity) Rescue (SAFER) during an untethered spacewalk. Middle: Astronaut Carl J. Meade tests the SAFER during an untethered spacewalk. Right: Meade, left, tests the ability of the SAFER to stop his spinning as Lee looks on.

Left: Astronaut Mark C. Lee tests the Simplified Aid for EVA (Extravehicular Activity) Rescue (SAFER) during an untethered spacewalk. Middle: Astronaut Carl J. Meade tests the SAFER during an untethered spacewalk. Right: Meade, left, tests the ability of the SAFER to stop his spinning as Lee looks on.

The main tasks of the spacewalk involved testing the Simplified Aid for EVA (Extravehicular Activity) Rescue (SAFER), a device designed at JSC that attaches to the spacesuit’s Portable Life Support System backpack. The SAFER contains nitrogen jets that an astronaut can use, should he or she become untethered, to fly back to the vehicle, either the space shuttle or the space station. The two put the SAFER through a series of tests, including a familiarization, a system engineering evaluation, a crew rescue evaluation, and a precision flight evaluation. During the tests, Lee and Meade remained untethered from the shuttle, the first untethered spacewalk since STS-51A in November 1984. Lee and Meade successfully completed all the tests and gave the SAFER high marks. Astronauts conducting spacewalks from the space station use the SAFER as a standard safety device. Following the 6-hour 51-minute spacewalk, the astronauts raised the shuttle’s atmosphere back to 14.7 psi.

A selection of STS-64 crew Earth observation photographs. Left: Mt. St. Helens in Washington State. Middle left: Cleveland, Ohio. Middle right: Rabaul Volcano, Papua New Guinea. Right: Banks Peninsula, New Zealand.

A selection of STS-64 crew Earth observation photographs. Left: Mt. St. Helens in Washington State. Middle left: Cleveland, Ohio. Middle right: Rabaul Volcano, Papua New Guinea. Right: Banks Peninsula, New Zealand.

Like on all space missions, the STS-64 astronauts spent their spare time looking out the window. They took numerous photographs of the Earth, their high inclination orbit allowing them views of parts of the planet not seen during typical shuttle missions.

Left: The Solid Surface Combustion Experiment middeck payload. Middle: Jerry M. Linenger gets in a workout while also evaluating the treadmill. Right: Inflight photograph of the STS-64 crew.

Left: The Solid Surface Combustion Experiment middeck payload. Middle: Jerry M. Linenger gets in a workout while also evaluating the treadmill. Right: Inflight photograph of the STS-64 crew.

In addition to their primary tasks, the STS-64 crew also conducted a series of middeck experiments and tested hardware for future use on the space shuttle and space station.

![]()

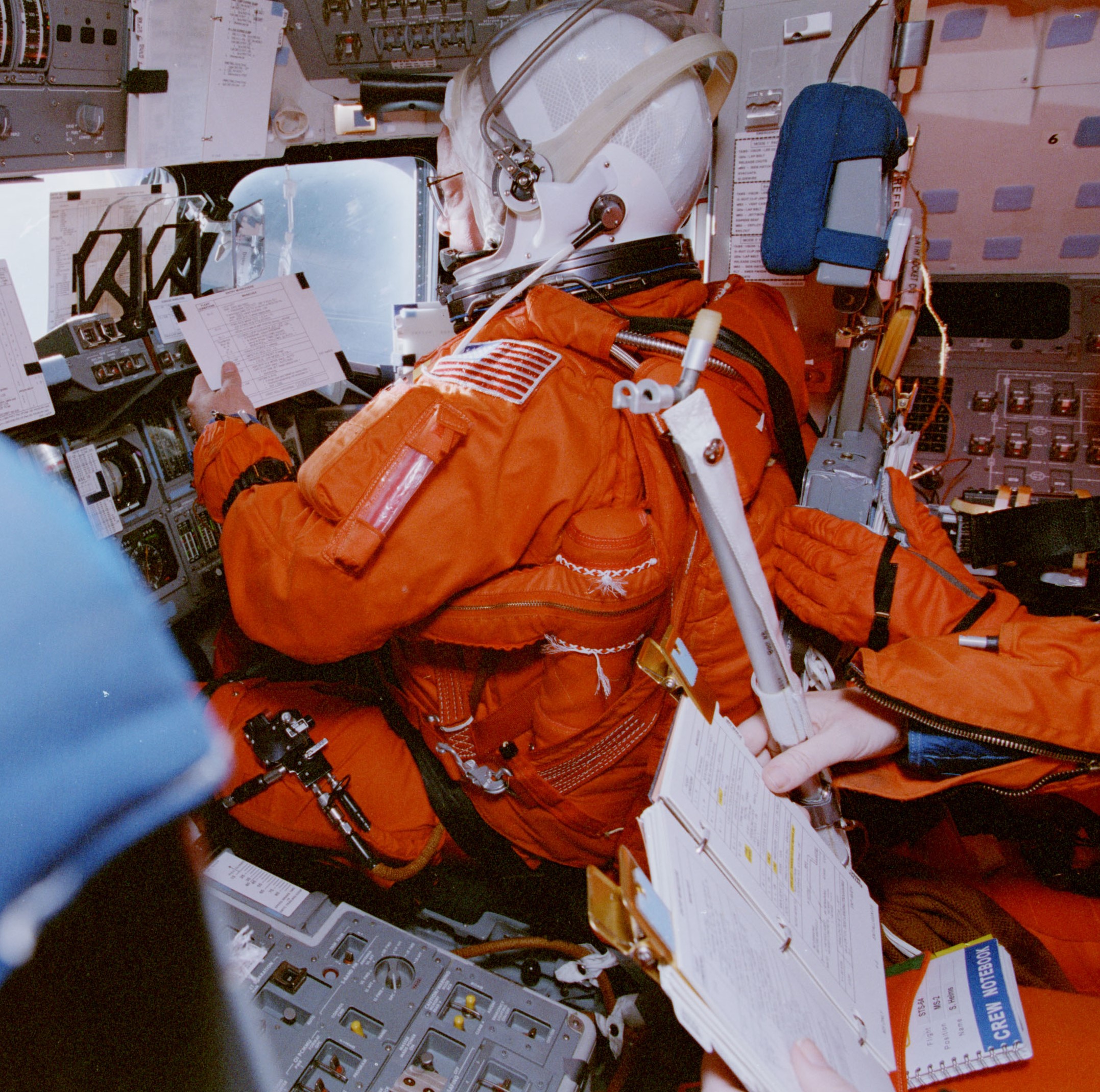

Left: Commander Richard “Dick” Richards suited up for reentry. Middle: Pilot L. Blaine Hammond, left, and Mission Specialists Carl J. Meade and Susan J. Helms prepare for reentry. Right: Hammond fully suited for entry and landing.

Left: Commander Richard “Dick” Richards suited up for reentry. Middle: Pilot L. Blaine Hammond, left, and Mission Specialists Carl J. Meade and Susan J. Helms prepare for reentry. Right: Hammond fully suited for entry and landing.

Mission managers had extended the original flight duration by one day for additional data collection for the various payloads. On the planned reentry day, Sept. 19, bad weather at KSC forced the crew to spend an additional day in space. The next day, continuing inclement weather caused them to wave off the first two landing attempts at KSC and diverted to Edwards Air Force Base (AFB) in California.

Left: Richard Richards brings Discovery home at California’s Edwards Air Force Base. Middle: Workers at Edwards safe Discovery after its return from STS-64. Right: Discovery takes off from Edwards atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft for the ferry flight to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

Left: Richard Richards brings Discovery home at California’s Edwards Air Force Base. Middle: Workers at Edwards safe Discovery after its return from STS-64. Right: Discovery takes off from Edwards atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft for the ferry flight to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida.

On Sept. 20, they closed Discovery’s payload bay doors, donned their launch and entry suits, and strapped themselves into their seats for entry and landing. They fired Discover’s OMS engines to drop them out of orbit. Richards piloted Discovery to a smooth landing at Edwards, ending the 10-day 22-hour 50-minute flight. The crew had orbited the Earth 176 times. Workers at Edwards safed the vehicle and placed it atop a Shuttle Carrier Aircraft for the ferry flight back to KSC. The duo left Edwards on Sept. 26, and after an overnight stop at Kelly AFB in San Antonio, arrived at KSC the next day. Workers there began preparing Discovery for its next flight, the STS-63 Mir rendezvous mission, in February 1995.

Enjoy the crew narrate a video about the STS-64 mission. Read Richards’ recollections of the mission in his oral history with the JSC History Office.