School board elections have evolved into a new arena of conflict in American politics, as traditionally nonpartisan contests are becoming more polarized and attracting national attention.

In suburban and rural Texas, normally mundane board meetings have devolved into shout-fests, and local school board campaigns have attracted well-heeled donors to tilt the scales.

Across Texas it’s now not uncommon for school board candidates to have political war chests in the tens of thousands of dollars, whereas before only four-digit sums were raised to send campaign mailers.

After the election of Joe Biden in 2020, the school board elections in Granbury, Texas took a partisan and culture-wars bent. Candidates like Courtney Gore campaigned openly as Christian, conservative, and, most importantly, as Republican.

Gore, a 43-year-old former GOP activist in her home county, said she worried the Granbury Independent School District curriculum was awash with liberal indoctrination, pressing “woke” cultural issues that included diversity, equity and inclusion and gender studies, as well as a school of study only offered in graduate level seminars: critical race theory.

When elected in 2021, Gore said she pored through the school programs.

“I didn’t find any CRT,” Gore said. “I didn’t find any sexualization of our children. It wasn’t even that there would be something taken out of context to be shown in a different light. They didn’t even come close to the stuff that I was hearing about.”

Gore said that there was “no there, there.” And when she relayed her findings that the curricula already reflected a fairly conservative community, she says fellow Republican activists met her with dismay and disbelief.

Gore said they called her political credentials in question.

“I’m conservative. I’m a Republican. I guess it depends on who you ask, locally,” Gore said. She added she’s been accosted by critics outside meetings and has even been confronted by people openly carrying firearms.

“There’s been instances where myself and other trustees have been threatened, and one citizen even went so far as to bring a gun to a school board meeting,” Gore said.

Gore said her party is engaging in purity tests and “eating its own.”

Her introspection is atypical of a movement to take over municipal politics, but her initial election fit a pattern of American school boards being politicized and charged with national issues — and big-money campaigns.

Julie Pace, an education policy researcher at the University of Southern California, has been taking the political and financial pulse of local school board elections. She says more money is being injected into them, especially in the suburbs, and they’re taking a more overtly political tone.

Pace said much of the energy is coming from conservative political action committees and wealthy donors, and adds that nonpartisans, centrists and liberal-leaning groups are only catching up.

In Houston’s suburban Cypress-Fairbanks schools, political action committees spent tens of thousands of dollars to usher in conservatives, like Natalie Blasingame.

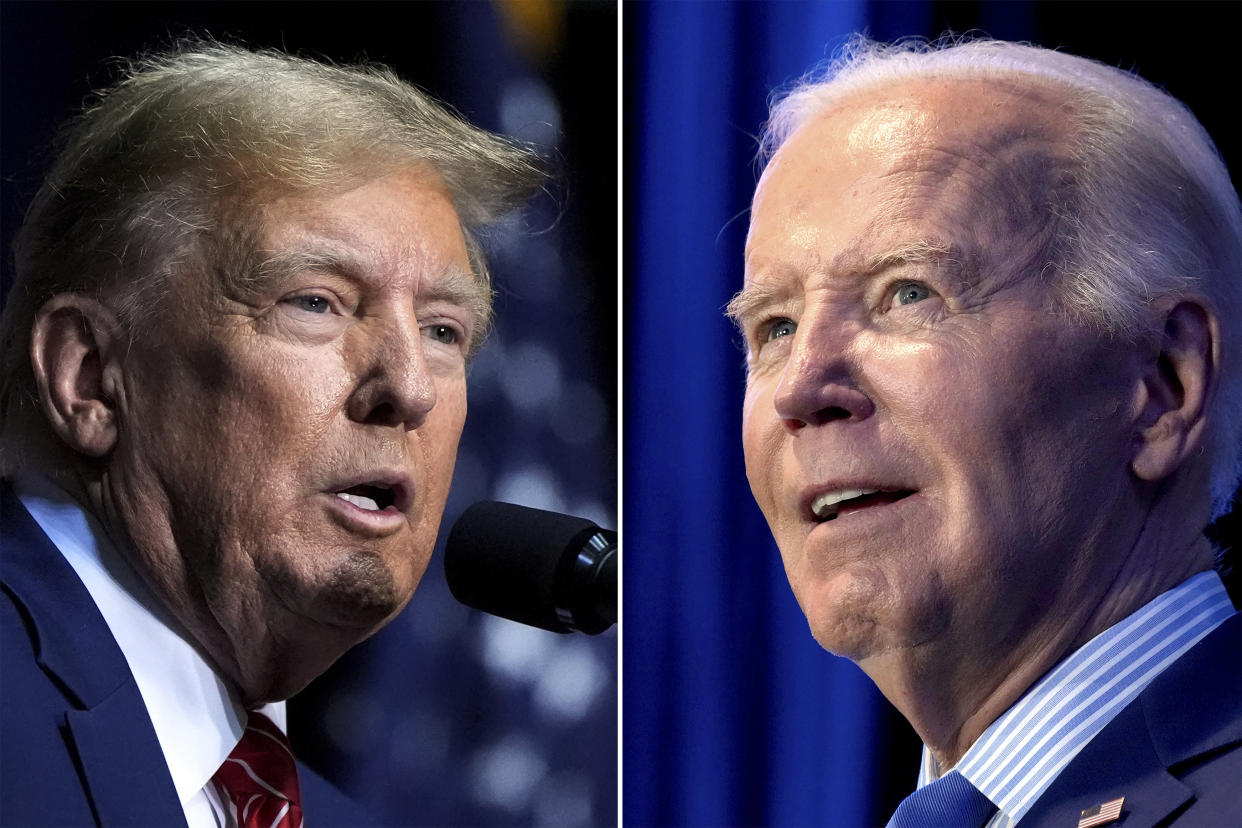

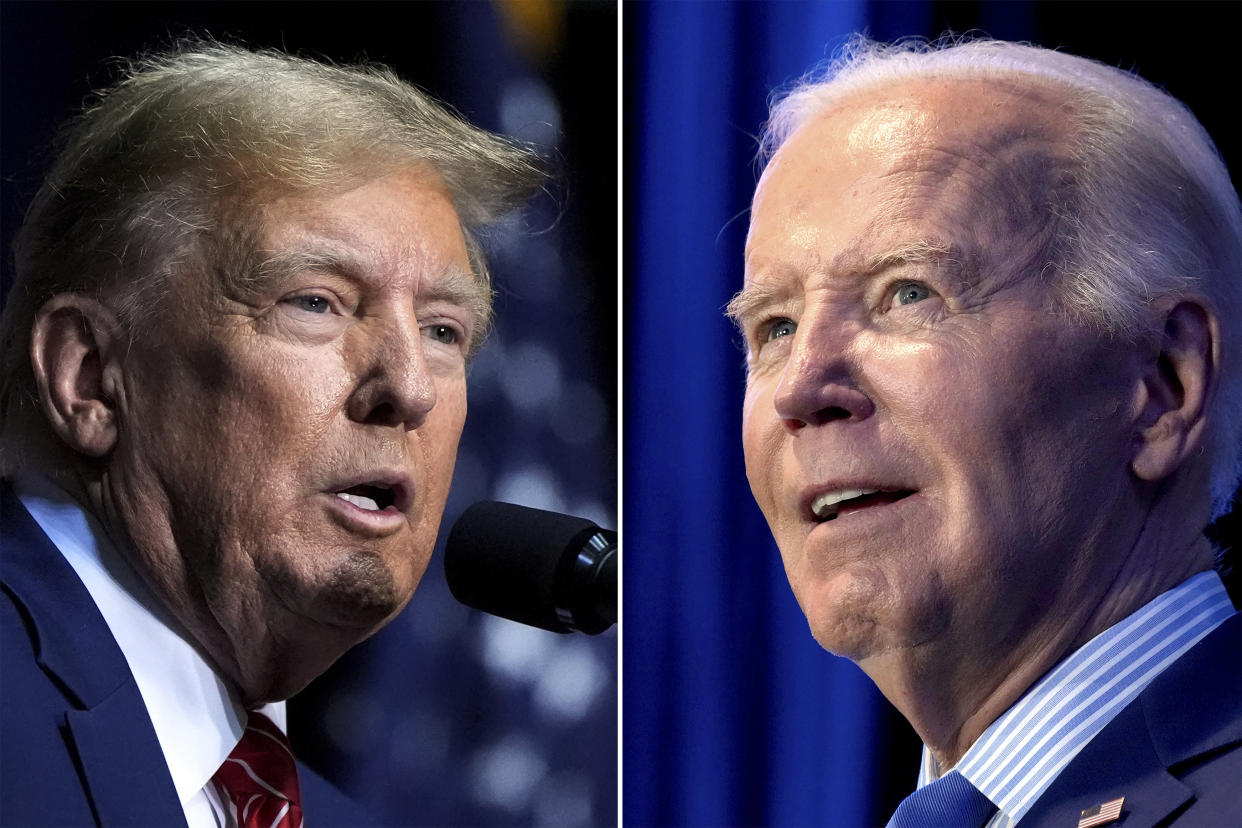

How do President Biden and former President Trump differ on education?

Earlier in May, Blasingame, who prior to her 2021 election campaigned openly as a Christian who wished “to bring God back on campus,” proposed eliminating and replacing chapters from state-approved science textbooks.

At the May 6 meeting of the Cypress-Fairbanks Independent School District board of trustees, Blasingame claimed, “An example is topics of depopulation, and an agenda out of United Nations in environmental science. There’s a lot around in population, and also, you know, a perspective that humans are bad.”

The board, which over the last two election cycles has shifted more partisan and more conservative, voted 6-to-1 to eliminate more than a dozen chapters.

Some critical parents say all the campaign cash produced a hostile takeover.

“[Blasingame] has stated publicly and in writing that she feels it is her calling by God to infiltrate the school system and bring the Christian, specifically the Christian religion and her specific beliefs, into our schools, and teach our children her personal beliefs that she feels called by God to do that,” said Cypress-Fairbanks parent Aly Fitzpatrick.

Blasingame did not respond to our request for an interview, nor did the school board president, Scott Henry.

Bryan Henry (no relation to Scott Henry) helps lead an opposition group called Cypress Families for Public Schools.The group is fiercely opposed to what they see as a religious-minded conservative takeover and a PAC-backed attempt to undermine faith in public schools. “They’re now using those votes, to do things that are out of step with the history of public education, and I would say even the values of the community,” Henry said.

Parent Jen Chenette, who regularly attends Cypress-Fairbanks board of trustees meetings, said the campaign finance records show a clear pattern.

“Those board members have their mouth wide open for all this money that’s poured in,” Chenette said, adding it’s tilted the policy priorities toward anti-science, and is veering towards book bans.

Courtney Gore sees a broader strategy in hyper-nationalizing the politics in hyper-local campaigns. “And it all boils down to this push that I’ve seen across the state, not just here in Texas, but actually nationwide for school vouchers,” Gore said.

The politicization of school boards in Texas dovetails with a yearslong fight the governor has waged to usher in school vouchers.

Texas campaign finance records show Abbott’s political campaign got a $6 million contribution in December from Pennsylvania investor billionaire Jeff Yass, a big proponent of school vouchers.

Despite the political battle within her own state’s GOP about vouchers, Gore said she remains a Christian conservative Republican who is a believer in public schools.