Explore

Who Wrote Texas’s Million Dollar, Bible-Infused Curriculum? The State Won’t Say

‘Someone knows this information,’ said a GOP member of the state board of education, citing a lack of transparency about the $84 million overhaul.

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

Almost three months after Texas sparked a firestorm of criticism for a new curriculum heavily infused with Bible lessons, state education officials still won’t say who authored the material or how much they were paid.

And because of the pandemic, they say they don’t have to.

A state official told The 74 that the work — an $84 million contract the state signed in March 2022 — falls under a disaster declaration Gov. Greg Abbott issued to speed up delivery of masks, vaccines and other critical supplies during the height of the pandemic. That means the paper trail that typically follows people who contract with the state, including work and payment reports, doesn’t exist in this case, the official said.

Some members of the state board of education, which will vote on the curriculum in November, are accusing education Commissioner Mike Morath and his staff of a lack of transparency.

“I did not get a lot of my questions answered when it came to who wrote the curriculum,” said Evelyn Brooks, a Republican board member whose district includes the Fort Worth suburbs. She’s one of at least three members who asked officials at the Texas Education Agency for more details. “It’s hard and it shouldn’t be. Someone knows this information.”

I did not get a lot of my questions answered when it came to who wrote the curriculum.

Evelyn Brooks, Texas Board of Education

Morath said the overhaul will bring classical education to over 2 million K-5 students in Texas. The model is designed to strengthen kids’ reading skills while also teaching them culture, art and history, including the Bible’s influence. Interviewed in early May, the commissioner would only say that “hundreds of people” worked on the project.

But that doesn’t satisfy board members who say the curriculum borders on proselytizing and promotes a distinctly evangelical view of American history.

A teacher’s guide for a third-grade lesson on ancient Rome, for example, devotes eight pages to the life and ministry of Jesus — presenting many of the events as historical facts, scholars say. But the Islamic prophet Muhammad isn’t named anywhere. A kindergarten lesson on “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” draws parallels to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. And an art appreciation lesson walks 5-year-olds through the creation story from the Book of Genesis.

“Who are the people that sat down in this fancy room and said this is the knowledge that every Texas student should have?” asked Staci Childs, a Democrat who represents the Houston area. She said she understands teaching the importance of religion in American history, but thinks the balance is off. “I just don’t think that it’s fair to have that many biblical references in the text in public schools across the state.”

The comments come a day before a Friday deadline for the public to submit feedback or suggest corrections to the curriculum.

Who are the people that sat down in this fancy room and said this is the knowledge that every Texas student should have?

Staci Childs, Texas Board of Education

Texas won’t force districts to use the materials, but is offering up to $60 per student — a total of $540 million — to any that adopt the program. That’s an incentive many are unlikely to turn down at a time school systems are projecting deficits and calling for tax increases to offset them.

The controversy is occurring against the backdrop of GOP support for teaching the Bible in several states, including Texas’s neighbors. A new Louisiana law requires schools to hang the 10 Commandments in classrooms, while Oklahoma state Superintendent Ryan Walters is mandating that educators use the Bible for instruction.

But no state has invested as much time and money as Texas in connecting its curriculum to Judeo-Christian messages.

As The 74 first reported in May, Morath signed a contract for K-5 reading and K-12 math materials with the Boston-based Public Consulting Group. In turn, the organization subcontracted with curriculum writers and experts, including officials at the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation and Hillsdale College.

At Hillsdale, Kathleen O’Toole, who leads work with charter schools affiliated with the Christian college, said her team only “offered resources on a few units having to do with early American history.” The college performed the work for free, she said.

The Texas Public Policy Foundation declined to comment on its role.

The contract Morath signed with the Public Consulting Group requires the company to submit monthly progress reports “documenting all subcontractor payments.” But when The 74 requested the documents in June under the state’s Public Information Act, Sherry Mansell, a coordinator in the general counsel’s office, said the state dropped the requirement because of the governor’s pandemic emergency order. The absence of those spending reports “understandably could cause some confusion,” Mansell wrote in an email. In a follow-up, she said the agency is “ensuring we receive the goods and services as specified in our contract.”

The Public Consulting Group did not respond to phone calls or emails.

When Mansell said no reports were available, The 74 asked an education agency spokesman to identify who wrote the new lessons and how much they were paid.

He didn’t respond until asked again Tuesday night. This time, he replied “absolutely” when asked if the public had a right to know the information and emailed a series of zip files containing over 100 pages of Public Consulting Group invoices for the past three years. None of them contained details about the religious lessons’ authorship. Reached again Wednesday, the spokesman declined to address the matter further.

‘Political considerations’

If board members are expected to approve the materials in November, Brooks said, they should know who wrote them.

She isn’t the only Republican on the board with reservations. Pat Hardy, a longtime GOP board member, said the state developed the new materials to placate the far-right wing of the party, which has pushed hard in recent years to expand Christianity’s presence in public schools.

“They’re going to appeal to the Christian nationalists with their Bible stories. They’re just trying to gather votes,” said Hardy, who lost in the primary to a candidate who accused her of not being conservative enough. Nonetheless, she’ll remain in office for the vote on the curriculum in November.

The Republican members’ views could hold sway on a board where they retain 10 of the 15 seats. Morath needs at least eight members to vote yes on the proposed curriculum for it to pass.

O ther Republicans on the board were less outspoken. Tom Maynard, whose district includes Austin, said there are “definite positives” in the curriculum as well as some needed “cleanup,” but didn’t offer specifics. Keven Ellis and L.J. Francis said they would save their comments until after a September meeting when the board will review the materials.

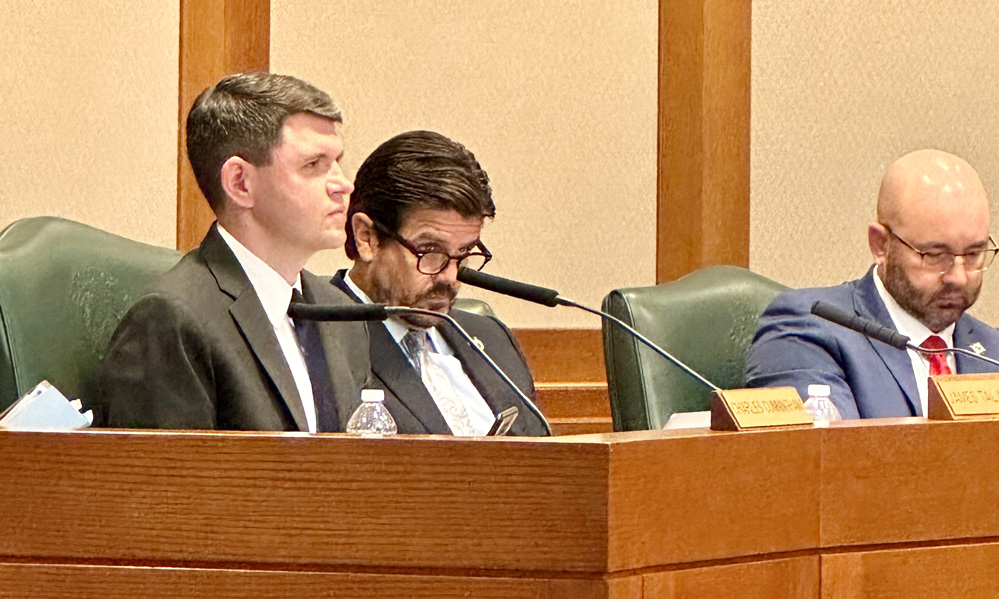

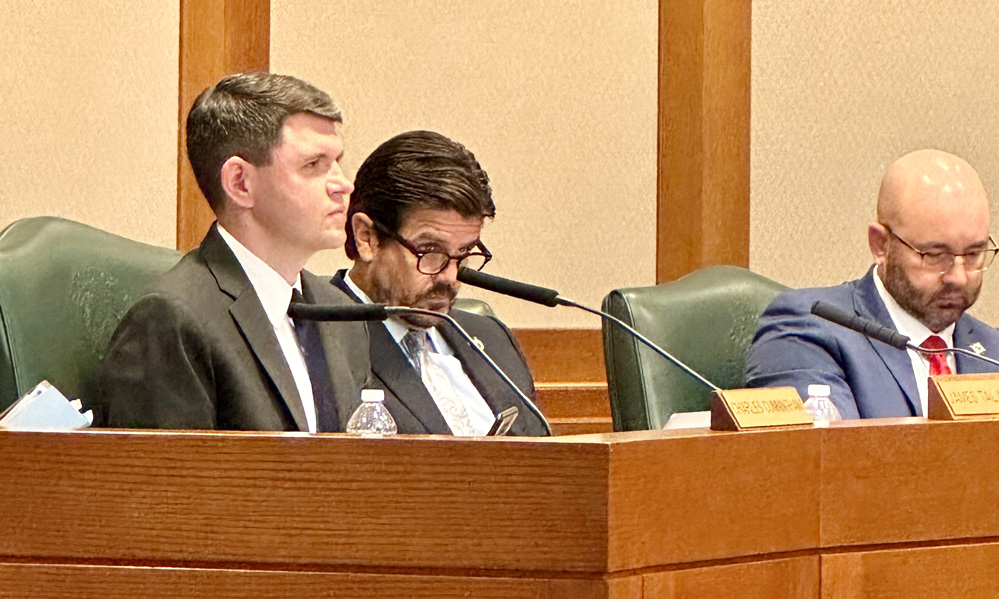

Questions about who wrote the biblical lessons are especially salient “when the curriculum is so shocking,” Democratic Rep. James Talarico, a seminary student and former teacher, told The 74. Talarico has been critical of the materials’ minimal attention to other world religions.

At a House education committee hearing Monday, he grilled Morath about whether “political considerations” influenced the overhaul. Talarico specifically named Tim Dunn, vice chair of the board of the Texas Public Policy Foundation and an oil magnate who has donated millions of dollars to conservative candidates — from Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump to voucher supporters running for the state legislature.

“Is the Texas Public Policy Foundation an expert in curriculum design?” Talarico asked the commissioner. He also noted that the state unveiled the material four days after the Texas GOP adopted a platform calling for required Bible instruction in public schools. “Are those two related?” he asked.

Morath dismissed the suggestion. The agency sought expertise from a “pretty broad swath of individuals,” he said. Those included experts in Texas history, which figures prominently in the curriculum. Lessons with engaging stories, including from ancient texts like the Bible, can improve students’ vocabulary and comprehension skills, he told the lawmakers. He shared data from Lubbock, one of the districts that piloted early versions of the curriculum, where the percentage of third graders meeting expectations increased from 36% in 2019 to 47% this year.

But Talarico questioned whether teachers are adequately trained to respond to student’s questions about religious topics raised in the curriculum like the Resurrection of Jesus and the Eucharist.

“When you’re talking about faith and you’re talking about theology, you’re working with fire,” he said. “These are serious topics. To me, this seems not only reckless, it seems that it could do great harm to students, whether they’re Christian or not.”

Republicans on the committee said their constituents have been “craving” such lessons.

Rep. Matt Schaefer rejected Talarico’s concerns that students of other faiths might feel left out. Other major world religions, like Islam and Hinduism, he said, “did not have an equal impact on the founding belief systems of our country.”

Biblical experts who have analyzed the new lessons, however, find inaccuracies and say some of the material is misleading.

The Texas Freedom Network, which describes itself as a “watchdog for monitoring far-right issues,” released an analysis of the curriculum Thursday, saying several lessons give students a distorted view of history.

The authors of the curriculum “smuggled” in lengthy passages on Christianity when a sentence or two would have been sufficient, David R. Brockman, a religious studies scholar at Rice University and the report’s lead author, said in an interview. He pointed, for example, to a reading from the Book of Matthew on the Last Supper as part of a fifth grade study of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting.

“I really wanted to keep an open mind,” he said, adding that the emphasis on the Bible makes sense when teaching students about Western civilization, but doesn’t help them learn to live in a diverse society. “Are they looking purely backward or are they looking forward? Texas students are not going to be living in 1787.”

Mark Chancey, a religious studies professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, said he submitted over 80 comments to the state. Some focus on a second grade lesson about Queen Esther, which talks about her faith in God, prayer and protecting the Jewish people’s freedom to worship.

The curriculum authors edited biblical material “to their liking to make it more religious,” he said. “The Book of Esther never mentions God, prayer or worship — not even once.”

His analysis of at least four other lessons that include Bible verses showed the authors exclusively relied on the New International Version of the text, a 1978 work he called a “distinctively evangelical translation” that was “made by evangelical scholars for evangelical Christians.”

A spokesman for the education agency did not address specific criticisms but said officials would examine potential inaccuracies revealed in the comments.

‘Will it teach students to read?’

Pam Little, another Republican board member, said her constituents are split “about 50-50” over the significance of the biblical material. Some conservative parents, she said, are upset “because they don’t feel like public schools are the place to teach Christianity.”

Will it teach students to read? For some reason, we seem to be having problems in Texas with that.

Pam Little, Texas Board of Education

But others, she said, are more concerned with whether the lessons will improve student performance. This year’s elementary test scores show there’s still a long way to go. The results were mixed, with declines in third and fifth grade and an increase in fourth.

The real question is “Will it teach students to read?” Little said. “For some reason, we seem to be having problems in Texas with that.”

Get stories like these delivered straight to your inbox. Sign up for The 74 Newsletter

We want our stories to be shared as widely as possible — for free.

Please view The 74’s republishing terms.

This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.

Almost three months after Texas sparked a firestorm of criticism for a new curriculum heavily infused with Bible lessons, state education officials still won’t say who authored the material or how much they were paid.

And because of the pandemic, they say they don’t have to.

A state official told The 74 that the work — an $84 million contract the state signed in March 2022 — falls under a disaster declaration Gov. Greg Abbott issued to speed up delivery of masks, vaccines and other critical supplies during the height of the pandemic. That means the paper trail that typically follows people who contract with the state, including work and payment reports, doesn’t exist in this case, the official said.

Some members of the state board of education, which will vote on the curriculum in November, are accusing education Commissioner Mike Morath and his staff of a lack of transparency.

“I did not get a lot of my questions answered when it came to who wrote the curriculum,” said Evelyn Brooks, a Republican board member whose district includes the Fort Worth suburbs. She’s one of at least three members who asked officials at the Texas Education Agency for more details. “It’s hard and it shouldn’t be. Someone knows this information.”

I did not get a lot of my questions answered when it came to who wrote the curriculum.

Evelyn Brooks, Texas Board of Education

Morath said the overhaul will bring classical education to over 2 million K-5 students in Texas. The model is designed to strengthen kids’ reading skills while also teaching them culture, art and history, including the Bible’s influence. Interviewed in early May, the commissioner would only say that “hundreds of people” worked on the project.

But that doesn’t satisfy board members who say the curriculum borders on proselytizing and promotes a distinctly evangelical view of American history.

A teacher’s guide for a third-grade lesson on ancient Rome, for example, devotes eight pages to the life and ministry of Jesus — presenting many of the events as historical facts, scholars say. But the Islamic prophet Muhammad isn’t named anywhere. A kindergarten lesson on “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” draws parallels to Jesus’s Sermon on the Mount. And an art appreciation lesson walks 5-year-olds through the creation story from the Book of Genesis.

“Who are the people that sat down in this fancy room and said this is the knowledge that every Texas student should have?” asked Staci Childs, a Democrat who represents the Houston area. She said she understands teaching the importance of religion in American history, but thinks the balance is off. “I just don’t think that it’s fair to have that many biblical references in the text in public schools across the state.”

The comments come a day before a Friday deadline for the public to submit feedback or suggest corrections to the curriculum.

Who are the people that sat down in this fancy room and said this is the knowledge that every Texas student should have?

Staci Childs, Texas Board of Education

Texas won’t force districts to use the materials, but is offering up to $60 per student — a total of $540 million — to any that adopt the program. That’s an incentive many are unlikely to turn down at a time school systems are projecting deficits and calling for tax increases to offset them.

The controversy is occurring against the backdrop of GOP support for teaching the Bible in several states, including Texas’s neighbors. A new Louisiana law requires schools to hang the 10 Commandments in classrooms, while Oklahoma state Superintendent Ryan Walters is mandating that educators use the Bible for instruction.

But no state has invested as much time and money as Texas in connecting its curriculum to Judeo-Christian messages.

As The 74 first reported in May, Morath signed a contract for K-5 reading and K-12 math materials with the Boston-based Public Consulting Group. In turn, the organization subcontracted with curriculum writers and experts, including officials at the conservative Texas Public Policy Foundation and Hillsdale College.

At Hillsdale, Kathleen O’Toole, who leads work with charter schools affiliated with the Christian college, said her team only “offered resources on a few units having to do with early American history.” The college performed the work for free, she said.

The Texas Public Policy Foundation declined to comment on its role.

The contract Morath signed with the Public Consulting Group requires the company to submit monthly progress reports “documenting all subcontractor payments.” But when The 74 requested the documents in June under the state’s Public Information Act, Sherry Mansell, a coordinator in the general counsel’s office, said the state dropped the requirement because of the governor’s pandemic emergency order. The absence of those spending reports “understandably could cause some confusion,” Mansell wrote in an email. In a follow-up, she said the agency is “ensuring we receive the goods and services as specified in our contract.”

The Public Consulting Group did not respond to phone calls or emails.

When Mansell said no reports were available, The 74 asked an education agency spokesman to identify who wrote the new lessons and how much they were paid.

He didn’t respond until asked again Tuesday night. This time, he replied “absolutely” when asked if the public had a right to know the information and emailed a series of zip files containing over 100 pages of Public Consulting Group invoices for the past three years. None of them contained details about the religious lessons’ authorship. Reached again Wednesday, the spokesman declined to address the matter further.

‘Political considerations’

If board members are expected to approve the materials in November, Brooks said, they should know who wrote them.

She isn’t the only Republican on the board with reservations. Pat Hardy, a longtime GOP board member, said the state developed the new materials to placate the far-right wing of the party, which has pushed hard in recent years to expand Christianity’s presence in public schools.

“They’re going to appeal to the Christian nationalists with their Bible stories. They’re just trying to gather votes,” said Hardy, who lost in the primary to a candidate who accused her of not being conservative enough. Nonetheless, she’ll remain in office for the vote on the curriculum in November.

The Republican members’ views could hold sway on a board where they retain 10 of the 15 seats. Morath needs at least eight members to vote yes on the proposed curriculum for it to pass.

Other Republicans on the board were less outspoken. Tom Maynard, whose district includes Austin, said there are “definite positives” in the curriculum as well as some needed “cleanup,” but didn’t offer specifics. Keven Ellis and L.J. Francis said they would save their comments until after a September meeting when the board will review the materials.

Questions about who wrote the biblical lessons are especially salient “when the curriculum is so shocking,” Democratic Rep. James Talarico, a seminary student and former teacher, told The 74. Talarico has been critical of the materials’ minimal attention to other world religions.

At a House education committee hearing Monday, he grilled Morath about whether “political considerations” influenced the overhaul. Talarico specifically named Tim Dunn, vice chair of the board of the Texas Public Policy Foundation and an oil magnate who has donated millions of dollars to conservative candidates — from Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump to voucher supporters running for the state legislature.

“Is the Texas Public Policy Foundation an expert in curriculum design?” Talarico asked the commissioner. He also noted that the state unveiled the material four days after the Texas GOP adopted a platform calling for required Bible instruction in public schools. “Are those two related?” he asked.

Morath dismissed the suggestion. The agency sought expertise from a “pretty broad swath of individuals,” he said. Those included experts in Texas history, which figures prominently in the curriculum. Lessons with engaging stories, including from ancient texts like the Bible, can improve students’ vocabulary and comprehension skills, he told the lawmakers. He shared data from Lubbock, one of the districts that piloted early versions of the curriculum, where the percentage of third graders meeting expectations increased from 36% in 2019 to 47% this year.

But Talarico questioned whether teachers are adequately trained to respond to student’s questions about religious topics raised in the curriculum like the Resurrection of Jesus and the Eucharist.

“When you’re talking about faith and you’re talking about theology, you’re working with fire,” he said. “These are serious topics. To me, this seems not only reckless, it seems that it could do great harm to students, whether they’re Christian or not.”

Republicans on the committee said their constituents have been “craving” such lessons.

Rep. Matt Schaefer rejected Talarico’s concerns that students of other faiths might feel left out. Other major world religions, like Islam and Hinduism, he said, “did not have an equal impact on the founding belief systems of our country.”

Biblical experts who have analyzed the new lessons, however, find inaccuracies and say some of the material is misleading.

The Texas Freedom Network, which describes itself as a “watchdog for monitoring far-right issues,” released an analysis of the curriculum Thursday, saying several lessons give students a distorted view of history.

The authors of the curriculum “smuggled” in lengthy passages on Christianity when a sentence or two would have been sufficient, David R. Brockman, a religious studies scholar at Rice University and the report’s lead author, said in an interview. He pointed, for example, to a reading from the Book of Matthew on the Last Supper as part of a fifth grade study of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting.

“I really wanted to keep an open mind,” he said, adding that the emphasis on the Bible makes sense when teaching students about Western civilization, but doesn’t help them learn to live in a diverse society. “Are they looking purely backward or are they looking forward? Texas students are not going to be living in 1787.”

Mark Chancey, a religious studies professor at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, said he submitted over 80 comments to the state. Some focus on a second grade lesson about Queen Esther, which talks about her faith in God, prayer and protecting the Jewish people’s freedom to worship.

The curriculum authors edited biblical material “to their liking to make it more religious,” he said. “The Book of Esther never mentions God, prayer or worship — not even once.”

His analysis of at least four other lessons that include Bible verses showed the authors exclusively relied on the New International Version of the text, a 1978 work he called a “distinctively evangelical translation” that was “made by evangelical scholars for evangelical Christians.”

A spokesman for the education agency did not address specific criticisms but said officials would examine potential inaccuracies revealed in the comments.

‘Will it teach students to read?’

Pam Little, another Republican board member, said her constituents are split “about 50-50” over the significance of the biblical material. Some conservative parents, she said, are upset “because they don’t feel like public schools are the place to teach Christianity.”

Will it teach students to read? For some reason, we seem to be having problems in Texas with that.

Pam Little, Texas Board of Education

But others, she said, are more concerned with whether the lessons will improve student performance. This year’s elementary test scores show there’s still a long way to go. The results were mixed, with declines in third and fifth grade and an increase in fourth.

The real question is “Will it teach students to read?” Little said. “For some reason, we seem to be having problems in Texas with that.”

On The 74 Today

;)