This article was originally published on August 24 by Deceleration, a nonprofit online journal producing news and analysis at the intersection of environment and justice.

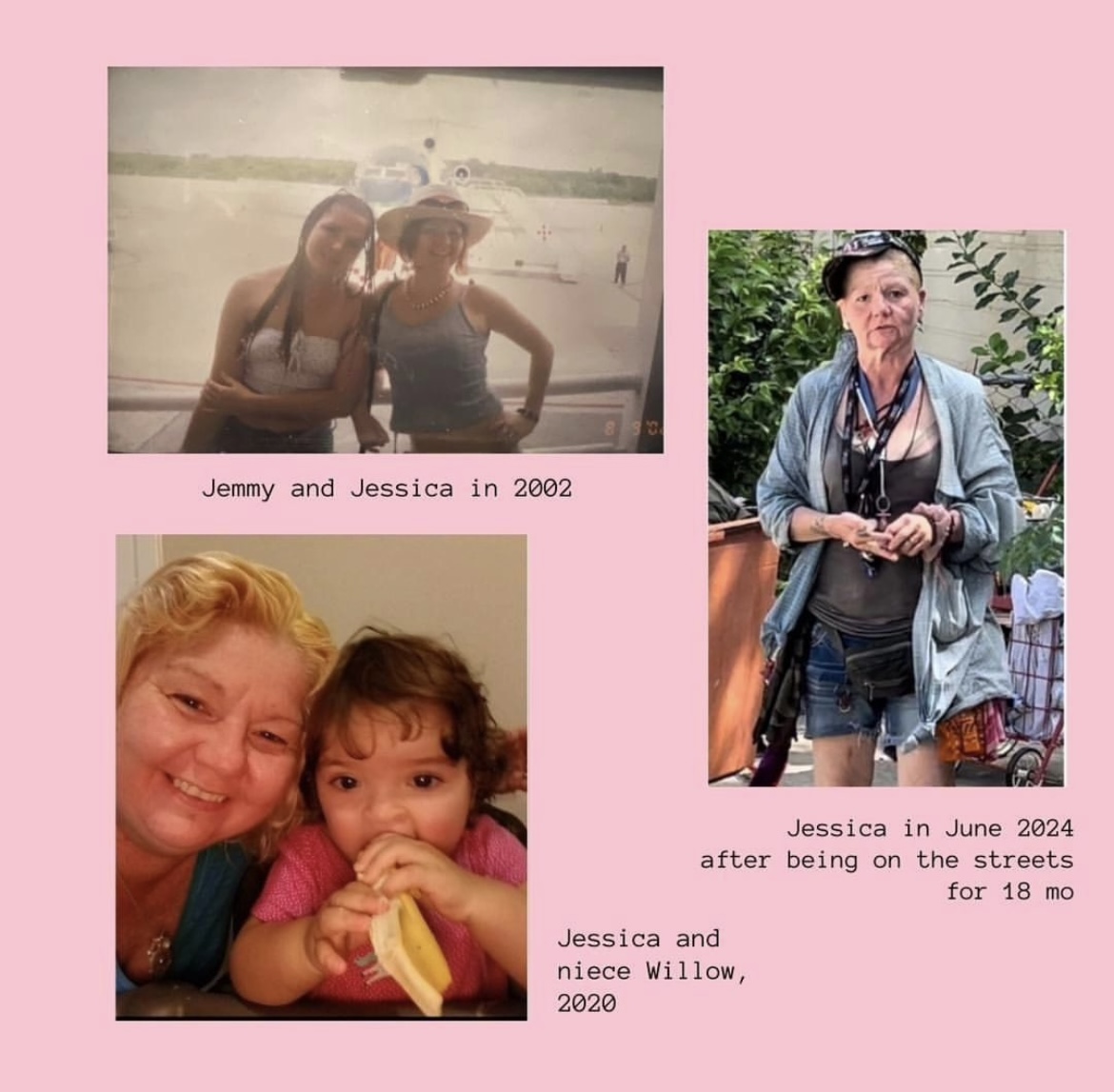

Deceleration Editor’s Note: On Thursday, August 22, 2024, a 46-year-old woman died on a sidewalk in the Five Points area of San Antonio in the midst of a brutal heat wave—an apparent victim of the day’s extreme temperatures. While the official high that day reached 106 degrees Fahrenheit, those temperatures are taken on the northside at San Antonio International Airport. Due to inequitable development patterns in urban areas and lots of heat-absorbing asphalt and concrete, temps across many more central neighborhoods are frequently much higher than what is recorded there. For example, Deceleration recorded heat index temps as high as 130 the day before in the downtown area. A family member confirmed to Deceleration that the woman was Jessica Witzel, a detail that has since been reported by other media. Deceleration Co-Editor Marisol Cortez had been supporting efforts to get Witzel, a family friend, off the streets and into medical care and stable housing. As Cortez writes here: Witzel’s death, much like that of Albert Garcia last summer, follows a pattern of lethally slow response time by local officials to the intertwined crises of climate, housing, and healthcare access for disabled people. — Greg Harman

Jessica Witzel was already at Bulverde Elementary when I arrived in 2nd grade, a new kid from San Antonio in a bizarre middle-of-nowhere rural landscape.

Jessica played flute in middle school band with me. She wore layers of black and purple lace and Wiccan necklaces and painted her fingernails black. She wore black T-shirts with the names of alternative bands on them: The Cure, Skinny Puppy. She was older and wiser, intimidatingly cool. She’d seen Morrissey live. What had he sounded like? I wanted to know. I was impressed.

His singing was impeccable, she said. He hit every note pitch perfect. Sounded just like his albums.

Jessica was a year ahead of me in high school. We were never close friends, but she hung out with kids I hung out with: the weird kids, the band kids, the art kids, the smart but troubled kids. She lived in a trailer with her younger sister Jemmy next door to one of my best friends in high school, a tall kid named Chris with a bowl haircut and preternatural artistic ability. It was Chris who introduced me to the kid who much later would become my older son’s dad, then my ex. But before that, Jessica was Miguel’s first love, his first real girlfriend.

Later, we lived above Jessica in a rented fourplex on E. Courtland, across from San Antonio College, where I moved right after college. She worked as an exotic dancer, which had intrigued me enough to interview her for a feminist theory class. She had exotic pets. A ferret, a parrot. Her apartment was cluttered and packed with stuff, an early sign of the hoarding struggles she would later develop.

“It really was her house, on some level. On some level, she was just trying to go home. “

Jessica was married, briefly, to a guy who was half Mexican and half white like us. I remember seeing their wedding photo, Jess in a long purple velvet dress holding her pregnant belly like she would a globe, with glitter on her eyelids and shoulder-length bob dyed red. She looked beautiful.

Jessica lived in different apartment complexes around town after she moved out of the fourplex, and sometimes we’d visit her. She spoke too fast and often so much it was hard to get a word in edgewise. She said she had been diagnosed bipolar, that she was taking medication.

Jessica wasn’t married long, but from that marriage she had one son, Antares—named for the brightest star in the constellation Scorpius, spoken with the Spanish pronunciation. Once we visited from California and hung out with Jess and another high school friend. Antares was about 18 months then, shy and sweet. I had never been around babies much as an adult and was enraptured with him. I followed him around and around the restaurant as he explored, feeling for the first time like I could imagine having a child of my own.

When we moved back to San Antonio from Kansas, Jessica was living on Blanco with Antares, then seven or eight, in a small two-bedroom duplex just south of Hildebrand, near the traffic circle. On returning to Texas, my ex moved in with Jessica temporarily while he looked for his own place, and when our four-year-old was with his dad, he’d stay with Jessica and Antares too. The duplex was small and crowded with stuff, like her other places had been, but the kids seemed happy. I remember going over and watching them play with a litter of kittens they’d named things like Black Shadow and Orange Ninja. Jessica’s son had a video game where you placed figurines from The Last Airbender on top of the console and the characters would magically appear on screen.

Eventually my ex found his own place, but Jessica remained a family friend until the end of her life—a sister to my ex, an aunt or godmother to my child. I was never as close to Jessica as they were, but I’d gone to school with her, I’d grown up with her.

Jessica died on the street in the heat on August 22, 2024. She’d been homeless for more than a year by that point, after losing the duplex on Blanco where she’d lived for years. She hadn’t been able to hold on to housing: she’d developed schizophrenia and had started lighting fires inside the house.

When I heard from my ex that she was on the streets, I asked him to connect me with Jess’ sister Jemmy. Maybe she knew where Jessica was. And if we could find her, maybe we could help.

So I reached out to Jemmy, hoping that what I’d learned from other mutual aid work I’d done with unhoused folks could possibly help Jessica too. Jemmy responded right away: Jessica was in Bexar County Jail, she said, where at least she was alive and off the streets and eating. But Jemmy was in hell, she said. For a year she had been calling and writing what felt like hundreds of people trying to get help for her sister—mental health services, shelters, attorneys, probate court, Adult Protective Services, 211, hospitals, jails, police. All to no avail.

She sent me pages and pages of documents, emails she had sent to county officials, jail officials, police. She sent me pictures of what Jessica had looked like before she became unhoused, after six months on the streets, another photo just before she was jailed in June. She’d dropped fifty pounds, Jemmy told me. She’d been raped on the streets, beat up, hit by cars.

The night Jessica was last arrested and jailed, she showed up at her old house insisting she owned it, that her mom, very much still alive, had died and given it to her. She threw clothes over the fence, pulled the fence down to enter the yard, collected things off neighbors’ porches and put them into a roller dumpster, took a hose and watered the neighbors’ houses. The neighbors called SAPD on her for trespassing and property damage, but to me something about these actions, distorted as they were through the filter of psychosis, carried within them some trace of the ordinary and domestic. It really was her house, on some level. On some level, she was just trying to go home.

Jemmy sent me Jessica’s rap sheet, the long list of prior charges that had accumulated in the time she’d been on the streets: sitting down in a right of way, camping in a public place, smoking outdoors where prohibited, littering. Reading them over, my heart sunk. Those weren’t crimes, not really. They were crimes like Jean Valjean stealing a goddamn loaf of bread to feed his starving family. Jessica wasn’t hurting anyone.

Jessica was ill. She needed immediate rehousing, food, the right kind of medical care so she could stabilize enough to stay safely housed. And nobody in any of the agencies her sister emailed and called for more than a year seemed to really give a fuck. While held in Bexar County, Jessica was supposed to have a psychiatric evaluation prior to her release back to the streets, which could have hastened her being deemed incapacitated and qualified her for guardianship, but it never happened. Jemmy called and called the court appointed attorney to follow up on this, but he never called back, she told me.

I’d reached out to Jemmy when I heard that Jessica was on the streets, because for a brief while we’d had some success getting our neighbor Albert Garcia housed. He’d lost his feet and part of one leg living unsheltered during Winter Storm Uri, and he would eventually die under a highway overpass in our neighborhood around this time last year, during a similar weeks-long stretch of triple-digit days. But for a time, neighbors and radical street medics, working together with determined people on the inside of institutional power, got a double amputee with a lifetime of heroin use off the street and sober for 18 months.

So I reached out to Jemmy. As with Albert, we started the process of applying for the Bexar County guardianship program that had saved Albert’s life for a time. I reached out to constituent services for District 5, where the jail was located, and later District 1, where Jessica hung out after release from jail, to request a meeting to discuss an emergency plan of action for connecting Jessica to resources and services. I reached out to mutual aid groups in the hopes street medics could establish regular check-ins with Jessica until guardianship came through. I tried connecting Jemmy with NAMI family support groups. We put together a direct aid request to raise funds.

Eventually, after several weeks of email follow up, District 5 politely declined to convene a meeting. There wasn’t really anything they could do, they said. Really it was on the County, they said, putting us in touch with Judge Oscar J. Kazen, who presides over Bexar County’s mental health court. I knew Kazen—he’d helped us with Albert, and he’d called us with his condolences when he heard Albert had died.

On the phone, Kazen was kind. He told us he would do what he could but that we needed to be realistic. It used to be there were public hospitals where unhoused people with serious mental illness could go to stabilize and rehabilitate, but those days were long gone. The only thing left was contract beds and voluntary care—of little help for people with schizophrenia, who frequently lack insight into their own condition and refuse treatment. If you really want to help, he laughed wryly, tell the City and County to build me a real psychiatric hospital.

Still, within a couple days of our conversation, Kazen’s office emailed Jemmy a legal document stating that Jessica had been assigned a guardian ad litem to represent her in court. Her case was moving. And for a couple days, we were hopeful.

Then the heat dome hit. And as with Albert when he returned to the streets last year at this time, the City and County moved too slowly for the pace and scale of the crisis we’re living.

I got the call yesterday. Between choking sobs, Jemmy read me what the news had reported about her sister, our friend. The day before, a 46-year-old woman, presumed to be unhoused, had been found unresponsive on a sidewalk in the Five Points neighborhood. Jemmy’s mother later confirmed with local authorities that the woman in the news reports was her daughter, Jessica Jill Witzel.

Initial reports of Jessica’s death state she died of natural causes resulting from heat-related illness. She died of what now? That’s like saying someone who lived below the levees and drowned during Hurricane Katrina died of natural causes.

The day before Jessica died, Deceleration’s heat monitoring downtown showed the heat index hitting a high of 130 degrees. According to Climate Central’s Climate Shift Index, this level of heat was made five times more likely because of anthropogenic climate change—meaning, essentially, this particular heat event was impossible but for the burning of fossil fuels and eradication of global forests that serve as carbon sinks. More simply stated, climate change is driving the extreme heat that killed Jessica. Climate change pulled the trigger. But institutional abandonment of the unhoused and disabled loaded the gun.

So no, it’s not underlying conditions that explain why someone like Jessica died in the heat, as some media reports of her death have suggested—even if, as an official cause of death is determined, this emerges later as a factor. It’s not the wrong kind of paving material, as suggested in a KENS 5 news story. Yes, how we build our cities matter. Which neighborhoods have access to shade and water matters. But big picture: It’s climate change. It’s deep histories of inequality. It’s systemic neglect of the most vulnerable.

We did this, in other words. We are doing this. But guess what. That means it can be different. That means it must be different.

The post The Woman Who Died in the Heat on a San Antonio Sidewalk Was My Friend appeared first on The Texas Observer.