Across the seven main battleground states in 2024, there are 10 counties — out of more than 500 — that voted for Trump in 2016 then flipped to Biden in 2020.

WASHINGTON — When you hear the term bellwether, you might think about states in the presidential election that always vote with the White House winner. The true meaning of a bellwether is an indicator of a trend. And for that, you need to be thinking about counties.

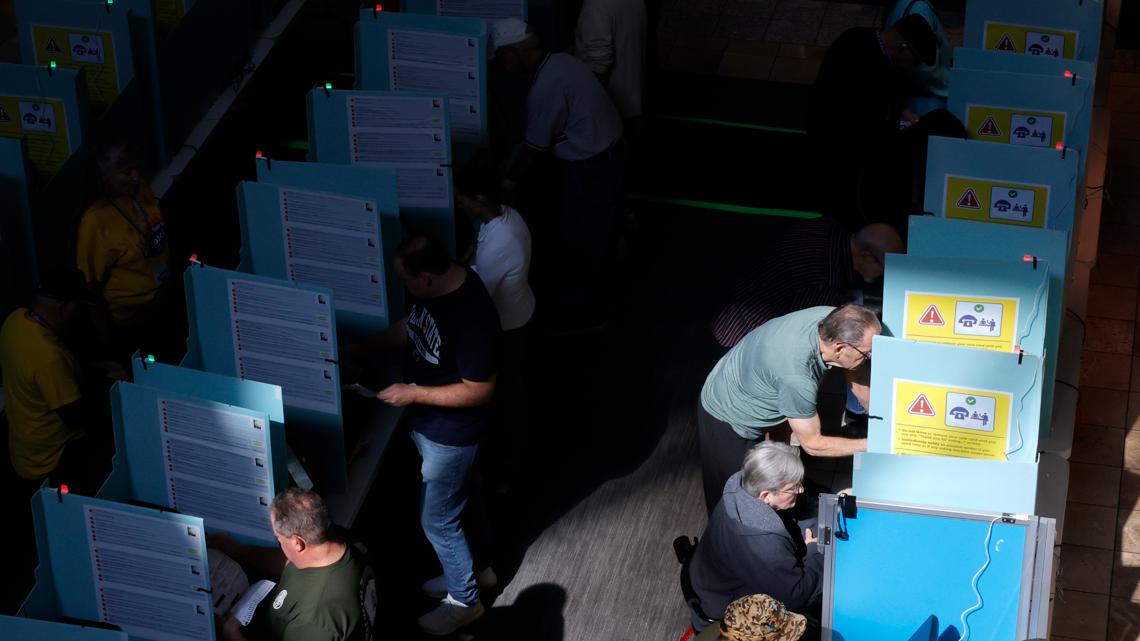

In a closely contested presidential election, as many expect 2024 to be, the results in a few bellwether counties in the key battleground states are likely to decide the outcome, just as they did in the past two general elections.

Here’s a look at those that might matter the most on Election Day.

Start with the cities

Many of those states have large, Democratic-leaning cities. These cities and their inner suburbs are an important source of Democratic votes in statewide elections. These areas consistently vote for the Democratic candidates, which means turnout in these places can have an outsized effect on the final statewide margin.

This year, look at Michigan’s Wayne County (Detroit), North Carolina’s Mecklenburg County (Charlotte) and Georgia’s Fulton County (Atlanta).

Republican candidates have tended to do well in the more rural areas of these states, which means Democrat Kamala Harris will need to run up big margins in these places in order to offset Republican Donald Trump’s advantage elsewhere.

Detroit, Charlotte and Atlanta are particularly large, about twice as populous as the next biggest municipality in each state. In 2020, voters in those three counties cast more than two-thirds of their votes for Democrat Joe Biden.

The suburbs matter

The turnout and margin in the counties around Milwaukee and Philadelphia will be significant to the results in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania, respectively.

In Wisconsin, the key counties that surround Milwaukee are Washington, Ozaukee and Waukesha — known colloquially as the “WOW” counties. These historically Republican-leaning communities have been slowly moving to the left: Republican presidential candidates have won them in recent elections, but by increasingly smaller margins.

This forces Republican candidates to seek to run up turnout in more rural areas of the state rather than relying on those counties to offset losses in the state’s urban counties of Milwaukee and Dane, home to Madison, the state capital and the University of Wisconsin’s main campus. It will be a good night for Trump if high turnout and margins in the “WOW” counties look more like the early 2000s, rather than 2020.

Philadelphia’s collar counties of Bucks, Montgomery, Chester and Delaware are among the state’s wealthiest. They, too, are historic Republican strongholds that have shifted left for decades. Democratic presidential candidates have carried three of them since the 1992 election; Chester flipped between the parties throughout the 2000s.

The massive counties

Arizona and Nevada are unique because in both states, one county is home to so much of the state’s population. More than 60% of ballots cast in the 2020 presidential election in Arizona came from Maricopa, which includes Phoenix, while more than two-thirds of Nevada votes came from Clark, home to Las Vegas.

In states where voters are so overwhelmingly concentrated in a single county, even a narrow win can produce big shifts in the statewide numbers. Biden won 50.3% of the vote in Maricopa in 2020, beating Trump by about 45,000 votes, and that was enough to win the state by just over 10,000 votes. In Nevada, Biden lost 14 of the state’s 15 counties, but his 91,000-vote margin over Trump in Clark was enough to secure his statewide victory of 34,000 votes.

Helene’s aftermath

Trump’s margin of victory in North Carolina was just 74,481 votes in 2020, a little more than 1 percentage point and the tightest of any state he won that year over Biden. It’s not yet clear, and may not be by Election Day, Nov. 5, how Hurricane Helene will affect the election in North Carolina.

The storm’s impact was severe in Buncombe County and the Asheville area, one of two counties in western North Carolina carried by Biden four years ago. The other counties in the region are reliably Republican, and suffered alongside Buncombe a level of destruction described by the state’s governor, Democrat Roy Cooper, as “unlike anything our state has ever experienced.”

“We’ve battled through hurricanes and tropical storms and still held safe and secure elections, and we will do everything in our power to do so again,” Karen Brinson Bell, the executive director of the state’s election board, said a few days after Helene struck. “Mountain people are strong, and the election people who serve them are resilient and tough, too.”

The swing counties

Across the seven main battleground states in 2024, there are 10 counties — out of more than 500 — that voted for Trump in 2016 then flipped to Biden in 2020. Most are small and home to relatively few voters, with Arizona’s Maricopa a notable exception. So it’s not likely they’ll swing an entire state all by themselves.

What these counties probably will do is provide an early indication of which candidate is performing best among the swing voters likely to decide a closely contested race. It doesn’t take much for a flip. For example, the difference in Wisconsin, in both 2016 and 2020. was only about 20,000 votes.

North Carolina’s two Trump-Biden counties – New Hanover on the Atlantic Coast and Nash, northeast of Raleigh – are likely to be the first among the 10 to finish counting their vote on election night. Polls close next in Michigan’s Kent, Saginaw and Leelanau counties and Pennsylvania’s Erie and Northampton counties, followed by Wisconsin’s Sauk and Door. Maricopa is the closer.

Associated Press writers Robert Yoon and Ali Swenson contributed to this report.

Read more about how U.S. elections work at Explaining Election 2024, a series from The Associated Press aimed at helping make sense of the American democracy. The AP receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.