Young women had been disappearing from the streets of El Paso for months before the first bodies were discovered in the desert northeast of the city.

On September 4, 1987, police found the remains of Karen Baker and Rosa Maria Casio in shallow graves. The search for other missing women stretched into March of 1988, interrupted by nearly two feet of snowfall in December 1987, a weather anomaly still remembered whenever snow falls in West Texas. Four more victims of the so-called “Desert Killer” were discovered: Ivy Williams, Desiree Wheatley, Angelica Frausto, and Dawn Smith. The victims’ ages ranged from 14 to 24.

Five were discovered in the same square-mile patch of the Chihuahuan Desert, and the sixth less than a mile away. The bodies were badly decomposed, making the causes of death difficult to determine. Police linked them because of the proximity and similarity of the burial sites, as well as signs that some women had been sexually assaulted. As police dogs searched the area for more victims and the public fervor for answers grew, investigators had zeroed in on their prime suspect: David Wood.

Wood had a history with the El Paso Police Department. In 1976, when he was 19, he was arrested for indecency with a child. After pleading guilty, he was sentenced to five years in prison, and served only half that time. In 1980, he pleaded guilty to two separate rapes: one of an adult woman and one of a 13-year-old girl. He received concurrent 20-year sentences, but he got out seven years later on parole.

That same year, he was jailed on suspicion of another sexual assault, and he had become the prime suspect in the Desert Killer cases.

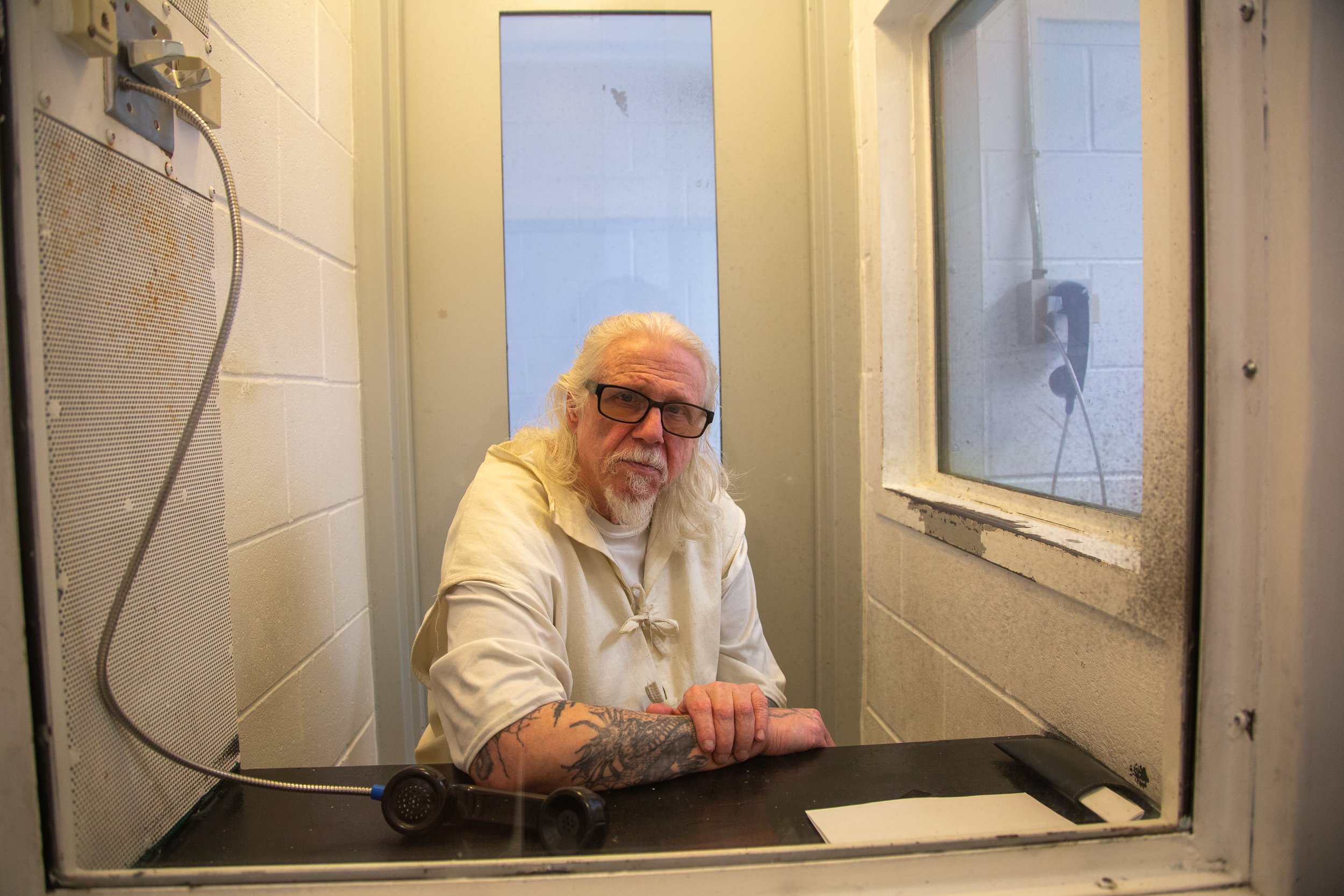

“Every time something would happen, [police] would pull me in,” Wood told the Texas Observer in a March interview. “They were accusing me of every unsolved crime on the planet. … My photo was everywhere. I didn’t stand a chance once I got arrested.”

The El Paso Police Department’s “Northeast Desert Murders Task Force” assembled a case against Wood. Officers found witnesses who saw Wood—or someone who fit his description—with some of the women around the time of their disappearances. They found fiber evidence that an investigator would testify linked Wood to one victim’s body.

While police built their investigation, Wood was convicted of sexually assaulting Judith Brown Kelling, a crime prosecutors argued fit the serial killer’s modus operandi. According to court documents, Kelling had previously identified a different man as her attacker. Wood’s attorneys have also offered up alibi witness accounts for him on the day Kelling was attacked, but he was convicted.

Wood was indicted for the murders of Williams, Wheatley, Baker, Frausto, Casio, and Smith.

Prosecutors won a conviction in the murder case based mainly on statements from two jailhouse informants who claimed Wood had confessed to them. At the time, the only DNA evidence authorities tested produced inconclusive results. The members of the El Paso jury were instructed only to determine whether he killed Williams and “one or more” of the other women; they didn’t need to specify or agree on which of the other killings they attributed to him. In 1992, the jury convicted Wood of capital murder and sentenced him to death.

“I want people to understand that I’m not looking for revenge,” Marcia Fulton, Desiree Wheatley’s mother, told an El Paso news station last year. “I’m looking for justice. He did the crime, he needs to do the punishment.”

Wood is scheduled to be executed March 13 in Huntsville. But he says the state got the wrong guy—and his lawyers say the case against him was built on an elaborate lie.

“I’ve been telling the truth ever since I got arrested, and no one’s ever listened to me,” Wood said. “I’ve been trying for 30 years to tell people I didn’t do this.”

As the date approaches, his lawyers are asking a court to consider evidence that Wood might actually be innocent, including a newer test that excluded Wood as the source of male DNA on one victim’s clothes. Wood’s attorneys have requested that more than 100 additional pieces of evidence be tested for DNA, but the state, represented by the Texas Attorney General’s Office, has opposed the request for over a decade.

His attorneys also cite reports that Wood’s trial lawyers never saw, which show Wood was being surveilled by Texas Rangers on the days that two victims—Angelica Frausto and Rosa Maria Casio—disappeared. The Rangers don’t mention Wood being with either woman. His truck was stored in a salvage yard and his motorcycle parked on the sidewalk under a tarp on the night Casio disappeared, according to court documents.

Those court filings reveal another bombshell: A former cellmate of one of the informants said he knows that the story that the state used to convict Wood—the purported jailhouse confession—was made up with the help of El Paso police.

In 1990, George Hall was moved from the Clements Unit, where he was then serving year 10 of a 45-year sentence for homicide, to the El Paso County Jail. He had no idea why he was being transferred—his crime had taken place in Hutchinson County, nearly 500 miles from El Paso.

Eventually, two other men showed up: Randy Wells and James Carl Sweeney. The three were placed in a holding tank, one that would normally house about 15 people.

Hall knew both men from his time at the Eastham Unit, a sprawling men’s prison in Houston County since renamed the J. Dale Wainwright Unit. The year before, he had shared a cell with Sweeney and, just down the row, Wells had shared a cell with David Wood, who was then serving 50 years for the sexual assault of Judith Brown Kelling.

While at Eastham, Sweeney had been helping Wood file a civil lawsuit against El Paso officials, claiming he had been unfairly targeted in the Desert Killer investigation. Wood’s sister sent more than 200 news articles to the prison for Sweeney to help draft the lawsuit.

In the holding tank at the El Paso jail, Wells told Hall he had been arrested for running a meth lab—which was untrue. Wells had been arrested on suspicion of murder. Not long after that arrest, Wells had called his attorney and said he had information about “bodies buried in the desert in El Paso.” Wells then apparently told police that they should talk to Sweeney and Hall.

“Wells told me and Sweeney that the cops wanted David Wood ‘real bad,’” Hall wrote in a sworn affidavit filed along with Wood’s appeal. “Wells said he could get his charges dropped if he could help the police. Wells asked us if we could tell him anything specific about the case.”

Eventually, two El Paso detectives brought the men into a conference room for questioning. On the wall, a photo of Wood was pinned up, surrounded by photos of the serial killer victims. The photos of the women were marked with their names, ages, and information about their disappearances and the discovery of their bodies.

According to Hall, detectives mentioned reward money—$25,000 from the El Paso Commissioners Court and another $1,000 from Crime Stoppers. He remembers detectives saying, “David Wood is our suspect. It’d be best if you tell us something because we can’t let this guy walk.”

Detectives then handed over their case files to the three men, court filings allege. Hall wrote in his affidavit that Sweeney and Wells read the documents, full of details that wouldn’t have been public knowledge, and then told police that Wood had confessed to “what they had just seen in the files.” Hall told officers that he wasn’t going to cooperate. “I said I wasn’t going to lie about David Wood.”

Thirty-five years later, in September 2024, Hall shared his story with Wood’s lawyers. He had waited decades because he was on parole until February 2024. But he had spoken up before, sending a letter to Debra Morgan, an El Paso assistant district attorney, the year before David Wood’s capital murder trial, that Wood’s defense team later obtained. Hall wrote, “I know Sweeney committed perjury before the grand jury and that Wells and him fabricated their stories together.”

Hall’s recollection of the methods police used to obtain jailhouse informant testimony casts serious further doubt on the state’s case.

Wells had been facing his own capital murder charge when he told police about Wood’s alleged jailhouse confession. Leslie Roberts was shot and killed in Eastland County in 1990, and Wells was arrested for her murder, along with two co-defendants. Wells brokered a deal: He would testify against Wood and against his co-defendants in the Roberts case. In exchange, the state dropped the capital murder charge against him. Wells was later indicted for aggravated perjury after providing conflicting statements about who pulled the trigger in the Roberts case.

Sweeney, the other jailhouse informant who testified, sued El Paso to get the reward money. The county eventually settled and cut him a check for $13,000.

Jailhouse snitch testimony is considered a red flag by many legal experts. According to the National Registry of Exonerations, 256 people who have been exonerated of felonies in the United States since 1989 were convicted in a case using jailhouse informant testimony. Sixteen were from Texas, including Federico Macias, who was convicted of murder and sentenced to death in El Paso in 1984. Macias was exonerated in the 1990s—after it was discovered that his conviction rested on false accusations and perjury.

Before David Wood’s capital trial in 1991, the state had three pieces of evidence tested for DNA. All tests came back inconclusive.

Nearly 20 years later, Wood’s lawyers asked for retests, and the state didn’t object. The results for two of the objects were still inconclusive. But in 2011, the lab’s test of a blood spot on a yellow terry-cloth outfit Dawn Smith was buried in revealed it came from another man—not David Wood.

One blood sample doesn’t prove Wood’s innocence. Because the jury was instructed that they had to find him guilty of Ivy Williams’ and “one or more” other murder, his exclusion as a suspect in the Dawn Smith case wouldn’t necessarily affect his conviction. After receiving that result, his lawyers requested more tests. But the state refused, calling further requests “absurd.”

“Wood’s requests were the very definition of a fishing expedition,” state attorneys wrote.

A state statute gives prisoners access to post-conviction DNA testing: Chapter 64 of the Code of Criminal Procedure. But after more than a decade of litigation, the trial court denied Wood’s request for testing in 2022. “I think they’re afraid of what they’ll find out,” said Greg Wiercoch, a clinical law professor at the University of Wisconsin and one of Wood’s appeals attorneys.

Along with untested pieces of evidence, investigators have not ruled out an alternative suspect—a man who failed a polygraph exam and lied about knowing multiple victims. Police collected samples from him back in 1987, but investigators never created a DNA profile for him, and his genetic profile has never been compared to the male DNA found on Smith’s clothing, according to court filings.

Forensically, only one piece of evidence tied Wood to a victim: orange fibers that police found on and around Desiree Wheatley’s body on October 20, 1987. Fibers weren’t found at the other burial sites, but police found similar fibers in a vacuum cleaner bag recovered from the garage of a building where Wood used to live. Police obtained the bag from a landlord several weeks after Wood moved out and a new tenant had moved in.

At Wood’s trial, a chemist from the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) testified that the fibers were a “match,” linking Wood and the crime scene. But other experts say it’s impossible to have that much certainty from fiber evidence. “In general, what fiber analysts can say is, ‘This is cotton, and it’s this color.’ They can take measurements of it and describe the characteristics,” said Kate Judson, executive director of the Center for Integrity in Forensic Sciences. “But in terms of matching it to a piece of evidence, there’s nothing to support that that’s accurate.”

More important forensic evidence was likely lost when investigators examined Ivy Williams’ body and used a cleaner—Clorox or something similar, according to court records—to remove tissue from the bones. They then scrubbed the bones with an abrasive pad, before the body had been examined by a forensic anthropologist to determine an estimated time of death for Williams, the only victim whose murder the jury had to agree on. Williams had never been reported missing, so those determinations were critical to the case.

“The discovery of Ivy Williams’s body in March 1988, over five months after David Wood’s arrest and incarceration, created a case-jeopardizing issue for the State: if Williams had disappeared and been murdered within the prior five months, David Wood could not be the Northeast Desert serial killer,” Wood’s lawyers wrote in an appeal document filed in February. Despite the flawed forensic examination, the state placed her death in May, making her the first victim of the Desert Killer.

Wood’s case has been in the appeals process since his conviction was handed down in 1992. His direct appeal was denied in 1995, as were multiple state and federal appeals over the next sixteen years. After the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear his case, he was first scheduled for execution on August 20, 2009.

The Texas Court of Criminal Appeals (CCA) halted that execution so the courts could determine whether Wood had an intellectual disability, which would disqualify him from being executed based on a 2002 Supreme Court ruling. The courts eventually determined he did not have an intellectual disability, but by that point his innocence claim and requests for DNA testing were already moving through the courts.

The current appeal, in which lawyers lay out Wood’s innocence claims, is pending before the CCA. Wood’s lawyers have also filed a clemency petition with the Board of Pardons and Paroles.

The post David Wood, Set for Execution, Says He Was Never the ‘Desert Killer’ appeared first on The Texas Observer.