As the judge and current district attorney clash over the case, the outcome could reshape the future of justice in Cooke County.

GAINESVILLE, Texas —

Outside the Cooke County Courthouse stands a monument to the Civil War.

Inside, a different kind of battle is unfolding in this deeply conservative county — one that could overturn a decades-old conviction.

At the center of the fight is District Judge Janelle Haverkamp, the former district attorney and now the county’s only elected felony court judge. In court filings, she is accused of withholding evidence in a 1997 capital murder case that sent Michael Newberry to prison for life.

What makes this case even more unusual? The current district attorney agrees.

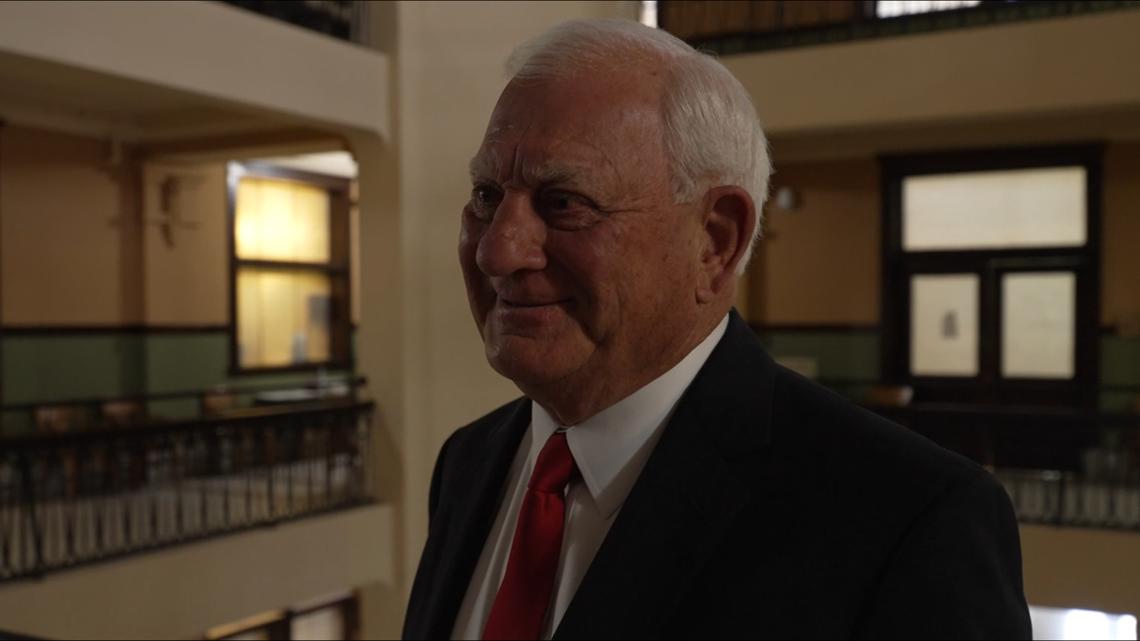

“When a prosecutor hides evidence, that dirties every other prosecutor,” John Warren, the current Cooke County District Attorney, told WFAA. “We won’t turn a blind eye to injustice.”

Court filings by Newberry’s attorneys paint a troubling picture. They claim his confessions were coerced, witnesses gave false testimony, and his own defense attorney had a secret conflict of interest. That attorney is now a county court at law judge, John Morris. He denies any wrongdoing.

The case sheds light on how courts operated before a 2013 Texas law required prosecutors to turn over all evidence to the defense. At the time of Newberry’s conviction, it was common for prosecutors to withhold key documents—like police reports and witness statements—unless a judge ordered otherwise.

Now, the key questions are: Did Newberry get a fair trial, and did Haverkamp, the former DA-turned-judge, follow the court’s order to share evidence that could have helped Newberry’s case?

Haverkamp and her supporters claim this is nothing more than a political attack by the current DA John Warren. She has asked the Texas Rangers to investigate Warren for alleged misconduct unrelated to the Newberry case.

“They have made horrible, heinous, false allegations against me,” Haverkamp testified last month. “This is all about a personal, political vendetta.”

Her testimony came during two days of tense courtroom hearings, presided over by visiting Judge Lee Gabriel. The judge will soon issue findings, which will then go to the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals. Their ruling will determine whether Newberry’s conviction stands or if justice demands a new trial.

The murder of 62-year-old Granville Hanks in 1996 started with a broken-down car and ended with a gunshot.

When Hanks’ vehicle stalled in Gainesville, he asked a group of young men for help. They refused. Minutes later, he was dead.

Investigators quickly turned their focus to two teenage gang members: Michael Newberry and Lilton Deon Moore. At trial, prosecutors told jurors that Newberry, 17, and Moore, 18, were riding with three friends when they came across Hanks, whose car had broken down.

What happened next remains disputed — both then and now, 28 years later.

Moore was the first to talk to police. He claimed Hanks had asked to buy crack.

“I said, ‘Nah, man, I ain’t got no crack,’” Moore told investigators, according to an audio recording of the interview. Then, he alleged, Newberry suggested robbing Hanks.

“I said, ‘Nah, I’m not gonna be a part of that,’” Moore recalled.

Moore said he gave the gun to Newberry; then, both approached Hanks.

“I said, ‘What’s up, man?’ … I turned around and heard Michael say, ‘Brace yourself.’ So I took off running back to the car. I heard a pow and just kept running.”

A detective pressed him.: “Did you actually see Newberry shoot Granville Hanks?”

“No, I didn’t see it,” Moore admitted. “But I know he had the gun.”

A month later, under oath before a grand jury, Moore changed his story. Now, he insisted they hadn’t planned to rob Hanks but approached him to sell drugs.

“They said, ‘Let’s go up there and serve him,’ like sell him some drugs,” Moore testified.

That distinction mattered. To convict Newberry of capital murder — an offense carrying an automatic life sentence — prosecutors had to prove the killing happened during a robbery.

Newberry’s attorney, Mark Lassiter, says the defense was never given Moore’s conflicting statements, preventing them from exposing inconsistencies that could have changed the case’s outcome.

On June 3, 1996, Michael Newberry turned himself in at the Cooke County Jail.

Records show that before starting the tape recorder, the detective spoke with him for 45 minutes. At a 1997 pretrial hearing, the detective testified he didn’t record that portion because Newberry didn’t want to talk. Newberry testified that he had asked for a lawyer, but the detective told him an attorney wouldn’t help. The detective denied that Newberry requested legal counsel.

On tape, the detective advised Newberry of his rights and asked if he wanted to waive them.

“No, sir,” Newberry responded.

“You said what?” the detective asked.

“Uh, no sir,” Newberry repeated.

“Do you understand what I’m saying?” the detective pressed.

“Not right there, that’s what I said,” Newberry replied.

“At that moment, the law requires the interview to be terminated because the suspect has chosen not to waive their rights,” Lassiter said. “This is a 17-year-old kid in a little room, interviewed without an attorney present.”

The detective later testified that he believed Newberry was confused so he tried to explain. However, the recording shows he never asked if Newberry understood what it meant to waive his rights.

During the recorded interview, Newberry said Moore got out of the car with a gun and a rag over his face. Moore demanded money, but the man refused.

“Deon kept pointing the gun at his head, and the next thing I know, I heard a shot,” Newberry said.

The detective turned off the recorder.

Later, he testified that he told Newberry he didn’t believe him.

“He hung his head down for a long moment,” the detective said. “Then he finally looked back up and said, ‘Yeah, I killed that man.’”

After a 37-minute break, the detective turned the recorder back on. Newberry’s story had changed—he confessed to shooting Hanks.

At the pretrial hearing, Newberry testified that he changed his story because he feared for his family’s safety.

His original defense attorney, John Morris, tried unsuccessfully to have the confession thrown out.

“He was under the influence of the police at the time,” Morris told WFAA last month. “There was nobody there to advise him because the confession was made before I ever got to be his lawyer.”

One of the men who had been in the car with Newberry and Moore guided police to the gun allegedly used in the killing. However, records show firearms testing failed to conclusively confirm it as the weapon that shot Hanks.

Jurors heard the confessions at Newberry’s 1997 trial. Morris argued that Moore was the real shooter, that there was no intent to rob Hanks and that it was a drug deal gone bad.

He asked the judge to let jurors consider the lesser charge of murder, which carries a sentence of five to 99 years. Capital murder, by contrast, carries an automatic life sentence.

The judge denied the request.

Jurors deliberated for about an hour and 20 minutes before returning a guilty verdict.

“You all was prejudiced, man,” Newberry said, according to the transcript. “A man can’t get no fair trial in this court.”

He then threatened Haverkamp in open court, saying that she “better be watching her (expletive) tonight cause she’s dead.”

The judge sentenced Newberry to life in prison. He later lost two appeals.

Moore pled guilty to aggravated robbery and received a 20-year sentence. He was released in 2016.

While serving life in prison, Newberry reconnected with his childhood friend Amber several years ago. She is now his wife and strongest advocate.

“He was still fighting for his freedom,” she said.

While reviewing police records, she read something that surprised her. A police report stated that Moore “talked to his attorney,” John Morris, before giving a statement to police — despite Morris later being appointed to defend Newberry.

“It’s called a conflict of interest,” said Lassiter, Newberry’s current attorney.

Ethical rules prohibit an attorney from representing two clients with potentially different interests. In criminal cases with co-defendants, if there is even a possibility of competing interests, an attorney cannot represent both defendants.

Morris told WFAA last month, “I don’t remember him (Moore) even calling me or any conversation with him.”

He suggested that Moore may have simply name-dropped him. He said that if Moore had called, he would have never advised him to speak to the police.

During the hearings last month, Lassiter also questioned Judge Haverkamp about a handwritten note found in the DA’s office files, that said, “John Morris let him talk.” He argues that it indicates that she knew about Morris’ alleged representation of Moore.

“I’m just making notes,” Haverkamp testified. “I’m not saying John Morris was his attorney.”

Several witnesses, including Moore, have recanted in notarized statements. One now says there was never a plan to rob Hanks. Another has taken back his claim that Newberry confessed.

“I wish to recant that I called this incident a robbery or said Michael had anything to do with the drug transaction and murder,” Moore’s statement said. “Nobody planned to rob anybody. It didn’t turn into a robbery either.”

In that new statement, he said that when he got out of the car to sell drugs to Hanks, Newberry went to a friend’s house. He said he and Hanks got into an argument.

However, Moore did not confess to shooting and killing Hanks.

The central question remains: Did Judge Haverkamp fail to disclose evidence that could have aided Michael Newberry’s defense?

In 1997, the original trial judge had ordered Haverkamp to turn over any evidence suggesting that someone else had fired or possessed a weapon in the Hanks case. Additionally, prosecutors were required to disclose any evidence “favorable” to Newberry.

“I never willfully withheld anything that I was required to turn over,” Haverkamp said.

When testifying, Haverkamp agreed that any evidence that could have disproved the robbery should have been shared. However, she didn’t believe any such evidence existed.

She testified that none of the statements or grand jury testimony would have benefited Newberry’s defense, and, therefore, she was not obligated to turn them over.

“I don’t know whether or not I did,” Haverkamp said when asked whether she disclosed the grand jury transcript as DA back then.

She testified that she had always been careful to follow the original trial judge’s order, adding that if she had believed Moore’s testimony would have helped Newberry, she would have disclosed it.

“You’re forgetting this defendant confessed twice,” she said in court.

She also said, “It is not a secret that Deon Moore possessed the gun.”

Lassiter told WFAA: “This is ensuring a conviction by making sure that the other side doesn’t have the information it needs to prove that’s not true.”

Morris testified at last month’s hearing that he never received Moore’s testimony or witness statements—information that, had he possessed it, would have altered his strategy.

He told WFAA afterward, that having those statements would have “made a big difference because it would have indicated other suspects.”

When asked if Newberry received a fair trial, Morris initially said yes. But when pressed on whether having those statements would have changed the outcome, he said, “I don’t know. I can’t answer that.”

For now, Haverkamp, who is Cooke County’s sole district court judge, has voluntarily recused herself from 120 pending felony cases.

She stepped aside after the current district attorney, who has accused her of misconduct in the Newberry case, argued in court documents that she is biased against his office. The motion alleges she yelled at his top assistant and created a hostile work environment.

In agreeing to recuse herself, Haverkamp said she was doing so because she filed “criminal complaints” against Warren and his office with the Texas Rangers and felt the need to recuse.

Visiting judges have been appointed to oversee cases.

It remains to be seen whether she will be required to recuse herself from 200 additional criminal cases. The DA is also requesting that she recuse herself from approximately 170 civil cases, including those related to asset forfeiture, protective orders and bond forfeiture.

Haverkamp declined to go on camera and answer WFAA’s questions. Via email, she said she had been “strongly advised” by the executive director of the State Commission on Judicial Conduct not to make “any public comments about this matter.”

However, Rick Hagen, an attorney representing Haverkamp, says Haverkamp has been a victim of an unjust attack.

“To present this case the way that it’s being presented, the false narrative that this man was convicted of a crime that he did not commit,” Hagen said. “I’m going to tell you that’s an insult and a slap in the face to every man and woman in this country that was wrongfully convicted.”

Warren denies politics are at play.

“I think that we need to keep our eye on what is important, and that is whether or not Mr. Newberry’s rights were violated,” he told WFAA.

Lassiter, Newberry’s current attorney, told WFAA he has filed a bar complaint against Haverkamp. He and Warren say she should face serious consequences for her handling of the Newberry case.

“That is playing with somebody’s life,” Warren said.

He vows to drop the charges against Newberry if the appeals court grants a new trial.

“If they decide that Mr. Newberry should receive a new trial…we will dismiss the charges against him and he will go free,” Warren said. “And I believe that after that, justice will have been served.”