Even after being diagnosed with brain cancer, Carter remained focused: “I’d like the last Guinea worm to die before I do,” he told reporters in 2015.

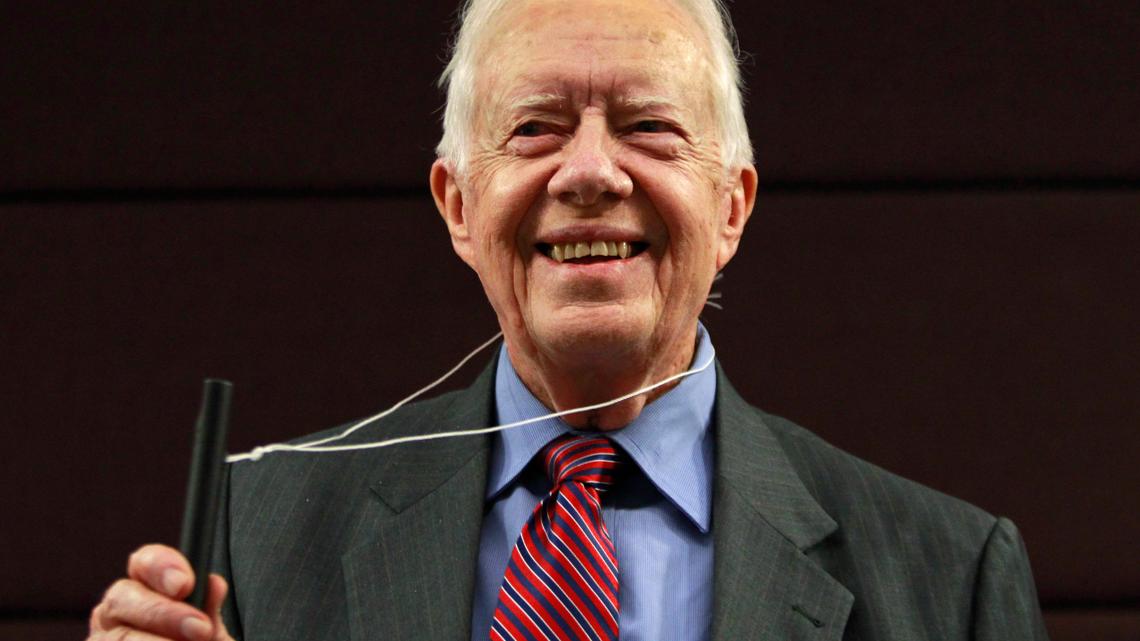

PLAINS, Ga. — Noble Prize-winning peacemaker Jimmy Carter spent nearly four decades waging war to eliminate an ancient parasite plaguing the world’s poorest people.

Rarely fatal but searingly painful and debilitating, Guinea worm disease infects people who drink water tainted with larvae that grow inside the body into worms as much as 3-feet-long. The noodle-thin parasites then burrow their way out, breaking through the skin in burning blisters.

Carter made eradicating Guinea worm a top mission of The Carter Center, the nonprofit he and his wife, Rosalynn Carter, founded after leaving the White House. The former president rallied public health experts, billionaire donors, African heads of state and thousands of volunteer villagers to work toward eliminating a human disease for only the second time in history.

“It’d be the most exciting and gratifying accomplishment of my life,” Carter told The Associated Press in 2016. Even after entering home hospice care in February 2023, aides said Carter kept asking for Guinea worm updates.

Carter died Sunday at age 100.

Thanks to the Carters’ efforts, the worms that afflicted an estimated 3.5 million people in 20 African and Asian countries when the center launched its campaign in 1986 are on the brink of extinction. Only 13 human cases were reported across four African nations in 2023, according to The Carter Center.

The World Health Organization’s target for eradication is 2030. Carter Center leaders hope to achieve it sooner.

That meant recently returning to Jarweng, in a remote area of South Sudan in northeastern Africa. The village of 500 people hadn’t seen Guinea worm infections since 2014, until Nyingong Aguek and her two sons drank swampy water while traveling in 2022. A fourth person also got infected.

“Having the worm pulled out is more painful than giving birth,” said Aguek, pointing to scars where four worms emerged from her left leg.

The center’s staff and volunteers walked house-to-house distributing water filters and teaching people to inspect dogs, which can also carry the parasite.

“If someone’s hurt, The Carter Center will help,” said villager Mathew Manyiel, listening to a training session while checking his dog for symptoms.

An audacious plan

In the mid-1980s, global health agencies were otherwise occupied and heads of state largely overlooked the illness afflicting millions of their citizens. Carter was still defining the center’s mission when public health experts who had served in his administration approached him with a plan to eliminate the disease.

Only a few years had passed since the WHO declared in 1979 that smallpox was the first human disease to be eradicated worldwide. Guinea worm, the experts told Carter, could become the second.

“President Carter, with a political background, was able to do far more in global health than we could do alone,” said Dr. William Foege, who led the U.S. Centers for Disease Control’s smallpox eradication program and the CDC itself before becoming The Carter Center’s first executive director.

Those who worked closely with Carter suspect Guinea worm’s toll on poor African farmers resonated with the former president, who lived as a boy in a Georgia farmhouse without electricity or running water.

“Nobody was doing anything about it, and it was such a spectacularly awful disease,” said Dr. Donald Hopkins, an architect of the campaign who led the center’s health programs until 2015. “He could sympathize with all of these farmers being too crippled from Guinea worm disease to work.”

Eliminating other diseases

There’s no vaccine that prevents Guinea worm infections or medicine that gets rid of the parasites. Treatment has changed little since ancient Greece. Emerging worms are gently wound around a stick as they’re slowly pulled through the skin. Removing an entire worm without breaking it can take weeks.

So instead of scientific breakthroughs, this campaign has relied on persuading millions of people to change basic behaviors.

Workers from the center and host governments trained volunteers to teach neighbors to filter water through cloth screens, removing tiny fleas that carry the larvae. Villagers learned to watch for and report new cases — often for rewards of $100 or more. Infected people and dogs had to be prevented from tainting water sources.

The goal was to break the worm’s life cycle — and therefore eliminate the parasite itself — in each endemic community, eventually exterminating Guinea worm altogether.

The campaign became a model for confronting a broader range of neglected tropical diseases afflicting impoverished people with limited access to clean water, sanitation and health care. Expanding its public health mission, the center has supplied training, equipment and medicines that helped 22 countries eliminate at least one disease within their borders.

Mali became the latest in May 2023 when the WHO confirmed it had ended trachoma, a blinding eye infection. Haiti and the Dominican Republic are working to eliminate malaria and mosquito-borne lymphatic filariasis by 2030. Countries in Africa and the Americas are pursuing an end to river blindness by 2035.

A personal mission

Having a former U.S. president lead the charge brought big advantages to a nonprofit that relied on private donors to fund its initiatives.

Carter’s fundraising enabled the center to pour $500 million into fighting Guinea worm. He persuaded manufacturers to donate larvicide as well as nylon cloth and specially made drinking straws to filter water. His visits to afflicted villages often attracted news coverage, raising awareness globally.

“He went to so many of the localities where people were afflicted,” said Dr. William Brieger, a professor of international health at Johns Hopkins University who spent 25 years in Africa. “The kind of attention that was drawn to him for getting on the ground and highlighting the plight of individual people who were suffering, I think that made an important difference.”

Carter first saw the disease up close in 1988 while visiting a village in Ghana where nearly 350 people had worms poking through their skin. He approached a young woman who appeared to be cradling a baby in her arm.

“But there was no baby,” Carter wrote in his 2014 book “A Call to Action.” “Instead she was holding her right breast, which was almost a foot long and had a worm emerging from the nipple.”

Carter used his status to sway other leaders to play larger roles. Some heads of state got competitive, spurred by the center’s charts and newsletters that showed which countries were making progress and which lagged behind.

Worms in a war zone

In 1995, Carter intervened when a civil war in southern Sudan made it too dangerous for workers to reach hundreds of hotspots. The ceasefire he negotiated enabled the center and others to distribute 200,000 water filters and discover more endemic villages.

Carter’s efforts not only stopped transmissions in much of what became South Sudan, but also built trust across communities that resulted in a “significant peace dividend,” said Makoy Samuel Yibi, the young nation’s Guinea worm eradication director.

Pakistan in 1993 became the first endemic country to eliminate human cases. India soon followed. By 1997, the disease was no longer found in Asia. By 2003, cases reported worldwide were down to 32,000 — a 99% decline in less than two decades.

Some setbacks frustrated Carter. Visiting a hospital packed with suffering children and adults amid a 2007 resurgence in Ghana, Carter suggested publicly that the disease should perhaps be renamed “Ghana worm.”

“Ghana was deeply embarrassed,” Hopkins said.

Ghana ended transmission within three more years. Even more inspiring: Nigeria, which once had the most cases in the world, reached zero infections in 2009.

“That was a thunderclap,” Hopkins said. “It was important throughout Africa, throughout the global campaign.”

To the last worm

Even after being diagnosed with brain cancer, Carter remained focused: “I’d like the last Guinea worm to die before I do,” he told reporters in 2015.

Despite dwindling cases, total success has proven elusive.

Historic flooding and years of civil war have displaced millions of people who lack clean drinking water across central Africa. Of the 13 total cases reported in 2023, nine occurred in Chad, where infections in dogs have made the worms harder to eliminate.

“These are the most challenging places on planet Earth to operate in,” said Adam Weiss, who has directed the campaign since 2018. “You need eyes and ears on the ground every single day.”

The campaign still relies on about 30,000 volunteers spread among roughly 9,000 villages. Staying vigilant can be difficult now that cases are so rare, Weiss said.

“I would still like to think we will beat the timeline,” Weiss said of the 2030 eradication goal. “The Carter Center is committed to this, obviously, no matter what.”

Bynum reported from Savannah, Georgia.