Money, according to Tim Dunn, only makes it “easier to perpetuate the illusion of control”.

In reality, the west Texas oilman drawled, each person is in control of only three things: “who or what you trust or depend on, how you look at things – your perspective – and what you do.”

“That’s it,” he said in a 2022 podcast interview with the evangelical group Promise Keepers.

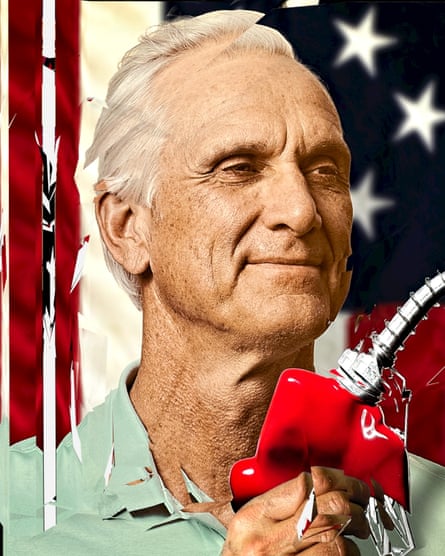

It’s a surprising statement from Dunn, an ultraconservative billionaire and pastor who has been called Texas’s “most powerful figure”. Over the past two decades, Dunn has poured approximately $30m into driving the state’s legislature to the far right.

Now the fossil fuel mogul and evangelical Christian is setting his sights on another target: the federal government.

Dunn established himself as the eighth-largest contributor to Donald Trump’s re-election campaign with a $5m donation in late 2023. He’s poured money into the far-right thinktanks the Center for Renewing America and America First Legal, led by Russell Vought, the former Trump budget director, and Stephen Miller, a former Trump senior adviser.

Dunn has also formed a business alliance with Brad Parscale, Trump’s former presidential campaign manager who recently bought a home in west Texas, and sits on the board of the America First Policy Institute – a policy incubator for Trump’s second campaign led by Brooke Rollins, his former domestic adviser. And Dunn serves on the board of the Texas Public Policy Foundation, a contributor to the rightwing, anti-regulatory policy blueprint for Trump called Project 2025.

Dunn may soon have an even larger fortune to funnel into rightwing causes. In December, weeks before he made his $5m contribution to Trump, Dunn agreed to sell his fracking company CrownRock – a partnership between his drilling firm CrownQuest and the private equity firm LimeRock – to Occidental Petroleum for $2.2bn. Federal regulators have held up the sale; if elected, Trump has promised to fast-track the deal and other similar mergers.

Though national politics are a new arena for Dunn, Texans say his reign in their state can shed light on his priorities in the federal sphere.

“This guy is an absolute white Christian nationalist, and he is willing to use his money to leverage exactly what he wants politically,” said Matt Angle, who directs the Lone Star Project, a Democratic political action committee in Texas.

Dunn rejects the Christian nationalist label, saying Christians should not “subjugate” their beliefs to other ideologies. He did not respond to requests for comment.

“Politics and religion are inseparable,” he said at a 2022 political convention. “You can’t have one without the other.”

‘Internalized a politics of religiosity’

Dunn was not born a billionaire. He grew up with three older brothers in the west Texas town of Big Spring, which sits on the edge of the world’s most productive oilfield, the Permian basin.

His parents did not graduate from high school. Dunn’s father worked on farms and factories in California, moving to Texas after the second world war to work in insurance sales.

When Dunn was born in 1955, his once-sleepy hometown was booming as thousands moved in to work at a reopened military base, petrochemical firms and the largest oil refinery in the region. As a young man he regularly attended church with his family, and through high school played on sports teams and in rock bands.

“I harbored the ambition to be a professional athlete, a professional musician, and a company president,” he wrote in his 2018 memoir, Yellow Balloons. “Though I didn’t have the aptitude or the required commitment to become either a professional athlete or musician, I did have an aptitude for business.”

After graduating from high school in 1974, Dunn headed north to Texas Tech University to study chemical engineering. Three years in, he got married and soon after had his first child.

When he graduated, Dunn took a job at Exxon in Houston and then for a brief stint managed oil companies’ books at a bank – a job that brought him to his current home of Midland, Texas.

Read more on the election operators shaping Trump’s White House bid:

-

Steve Bannon: his War Room podcast is shaping the Republican narrative

-

Charlie Kirk: Republicans are turning on the former youth guru

-

Kevin Roberts: the force behind Project 2025

-

Cleta Mitchell: the ex-Democratic firebrand turned election denier

-

Hans von Spakovsky: the man who cries voter fraud

In 1987, he returned to the fossil fuel industry as an executive at a newly opened drilling company, Parker and Parsley Development Partners, but stepped down eight years later amid turmoil at the company. Parker and Parsley later became top Permian oil business Pioneer Natural Resources, which Exxon agreed to purchase last year in one of the largest US fossil fuel mergers in decades.

Dunn went on to co-found his own fossil fuel company – and began his foray into politics. In 1996, he was a delegate to the Texas Republican convention, Texas Monthly reported. That same year, he began buying up west Texas oil wells, which would prove highly valuable more than a decade later amid the hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) boom that has made the US the world’s top oil producer.

Ten years later, Dunn opposed a measure that would have imposed new taxes on business partnerships, including ones that fund oil wells. In 2006, he founded the conservative political organization Empower Texans to oppose the measure.

Dunn continued to use Empower Texans to write checks for rightwing causes for years. When the group was dissolved amid controversy in 2020 – the group’s higher-ups were caught making offensive jokes about Greg Abbott, the Texas governor – he began placing political funding into a new group, Defend Texas Liberty.

The Pac handed donations to an array of far-right issues and candidates, including former youth pastor Bryan Slaton, who was ousted from the state house last year over accusations of an inappropriate sexual relationship with an underaged aide. Then last fall, Defend Texas Liberty’s president – a former state legislator who had accepted hundreds of thousands of dollars from Dunn and his Pacs – met with white supremacist Nick Fuentes.

Dan Patrick, the Texas lieutenant governor, who had himself obtained $3m in campaign cash and loans from Dunn-backed groups, said Dunn acknowledged the meeting was a “blunder”. The Pac was soon shut down.

Within weeks it was replaced with a new group, Texans United for a Conservative Majority, helmed by Dunn and his frequent collaborator, fellow oil billionaire and evangelical Farris Wilks.

In April, Dunn once again came under fire when Texas’s former house speaker Joe Straus, who is Jewish, said the oil mogul told him in 2010 that only Christians should lead the Texas legislature – something Dunn has not publicly denied.

Dunn explicitly says he sees his political activity as an extension of his Christianity.

The oilman’s flavor of rightwing ideology is tied to his west Texas oilfield origin story, said Darren Dochuk, historian and author of Anointed With Oil: How Christianity and Crude Made Modern America.

“People like Dunn who have grown up on the west Texas oil patch have internalized a politics of religiosity that is more fiercely libertarian than we see anywhere else up to that point,” he said.

West Texas is isolated from economic and political hubs like Houston and Dallas, which can boost isolationist tendencies and encourage residents to “focus on their local communities, their families and their churches”, said Dochuk.

“It’s a frontier zone that has always encouraged a certain imagination of individualism and do-it-yourself capitalist verve, whether it’s for building a Baptist church or setting up an oil rig,” he said.

Dunn is now the father of six grown children, four of whom work at his oil company, CrownQuest. He lives in a mansion on a 20-acre Midland compound. Five of his six children and many of their grandchildren live in homes on the compound or elsewhere in town.

Around the corner is a private K-12 religious school that Dunn founded, Midland Classical Academy, which several of his children and grandchildren have attended. Four of his children also volunteer at Midland Bible church, which Dunn founded more than 25 years ago and where he still preaches.

‘Oil is at the center’

Dunn has referred to environmental advocates as “extremists” who “want to deindustrialize America” and “live in huts around a campfire”. The Texas Public Policy Foundation, of which he is vice-chair, has also spearheaded attacks on both environmentally focused financial policies and efforts to boost renewable energy.

He told Forbes he would like to see the Environmental Protection Agency dismantled. And the Project 2025 plan, to which the Dunn-tied Texas Public Policy Foundation contributed, includes roadmaps to uplift fossil fuels and broadly unmake environmental regulations.

But Dunn’s most visible pet issues are not directly energy-related. He’s placed more focus on social issues such as undercutting public education, funding religious schools with taxpayer money, and attacking access to abortion and gender-affirming care.

“It’s an extremist vision for Texas,” said Chris Tackett, a former school board member from Fort Worth who has spent years chronicling Dunn’s political donations and runs the watchdog TX Campaign Finance. “And he seems to not think you can be far right enough.”

Tackett first became aware of Dunn’s influence in 2014, when his state representative promised to support public education but, once elected, voted “out of the blue” against the school board’s recommendations. He began pulling campaign finance data from the Texas ethics commission and found the legislator was accepting funding tied to Dunn.

Tackett built a rudimentary database, tracking $30m Dunn has poured into Texas campaigns and committees since 2000, and that’s not including potential dark money contributions. His strategy is not to fight against Democrats, but rather support challengers to Republican lawmakers with whom he has policy disagreements.

Dunn-backed candidates have supported a successful effort to ban abortion and another restricting access to gender-affirming care. They have also backed bills to prohibit trans Texans from using gender-affirming bathrooms, eliminate property taxes and vaccine requirements, and restrict access to morning-after pills. And Dunn allies have pushed to post the Ten Commandments in all public classrooms, and to replace public education with private-school vouchers.

Dochuk, the historian, sees Dunn’s far-right social vision as inextricable from his interest in protecting fossil fuels, even though they may seem unrelated. Dunn’s fierce support for private religious schooling over public education, for instance, would allow evangelical extremism to “maintain its hegemony” amid increasing environmental concerns and ensure students learn reverence for the “free market”.

Texas oilmen before him have also supported rightwing social causes, with the head of Hunt Oil sponsoring the anti-communist John Birch Society and the anti-abortion pastor Francis Schaeffer. “They see a need to protect their whole way of life from the outside, and oil is at the center of that,” said Dochuk.

In his sermons, Dunn rails against Marxism, which he often calls the “spirit of the age”.

Marxists are “becoming bolder and more brazen in their quest for tyranny”, Dunn drawled at a 2019 talk at a conference organized by the far-right Convention of States, to which he has been tied since its founding. “It’s becoming clear they want to kill us.”

The statement exemplifies the fear of an “encroaching communism”, said Dochuk, that evangelical oilmen have long feared will come for their so-called family values and their oil – the lifeblood of their Texas homeland.

These fears jibe with Trump’s rhetoric on the campaign trail. But in other ways, the former president has broken with his evangelical supporters.

Dunn made no public contributions to Trump in 2016, instead supporting Senator Ted Cruz’s run. In 2020 he gave Trump $500,000 – just one-tenth of his most recent contribution.

Why would an ultraconservative Dunn back a presidential candidate who allegedly tried to hide hush-money payments to a adult film actor, has said he supports abortion in some cases and has been divorced twice? Angle, of the Lone Star Project, says he thinks Dunn is playing the long game, trying to take his brand of Texas conservatism national.

“He’s trying to move public money into the investor class,” he said. “He thinks Trump will help him do that … and he thinks he deserves it, because he thinks he’s rich because he is blessed.”

Though they may disagree about specifics, Angle said, Trump will likely allow Dunn to continue to wield his influence – and protect the energy sector through which he obtained it.

In Dunn’s 2022 interview with the evangelical Promise Keepers organization, he said: “Money is power to act. The key question is: what is it you want to do and what is it you want to accomplish?”