The fertilizer maker says its products are safe, and that the government supports using it as a valuable practice that recycles nutrients to farmland.

JOHNSON COUNTY, Texas — Ranchers here say their cattle, fish and horses are dying and getting sick because of a fertilizer spread on nearby farmland.

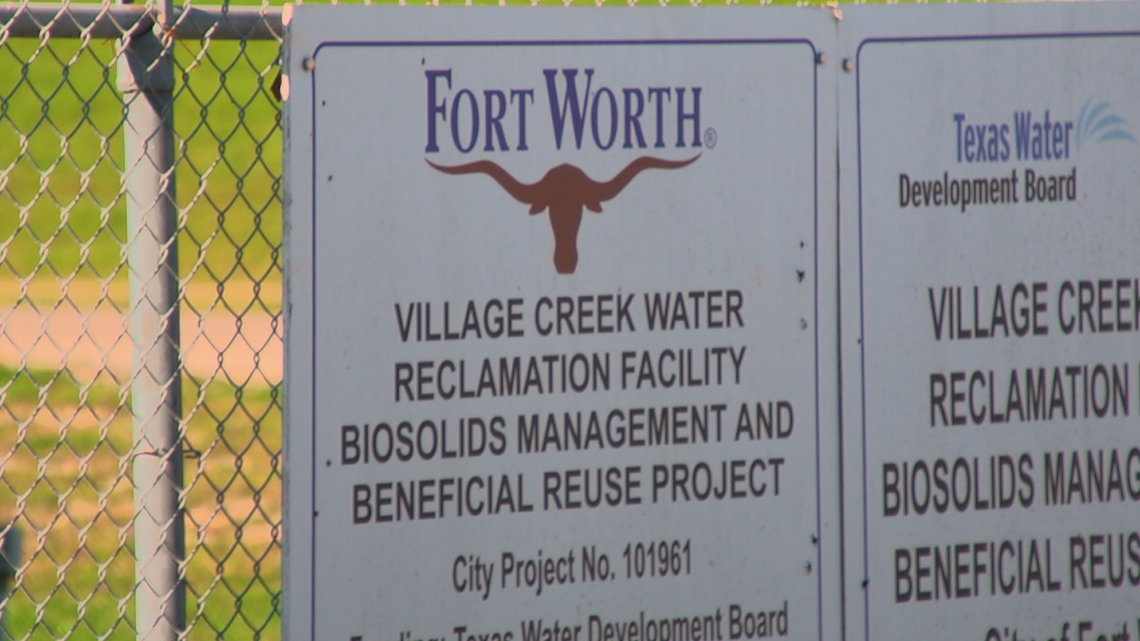

The fertilizer is made from treated human waste from the city of Fort Worth.

The company that makes the fertilizer says its products meet government standards.

County officials have launched a criminal investigation, and ranchers are suing, saying runoff from the fertilizer has made their land useless.

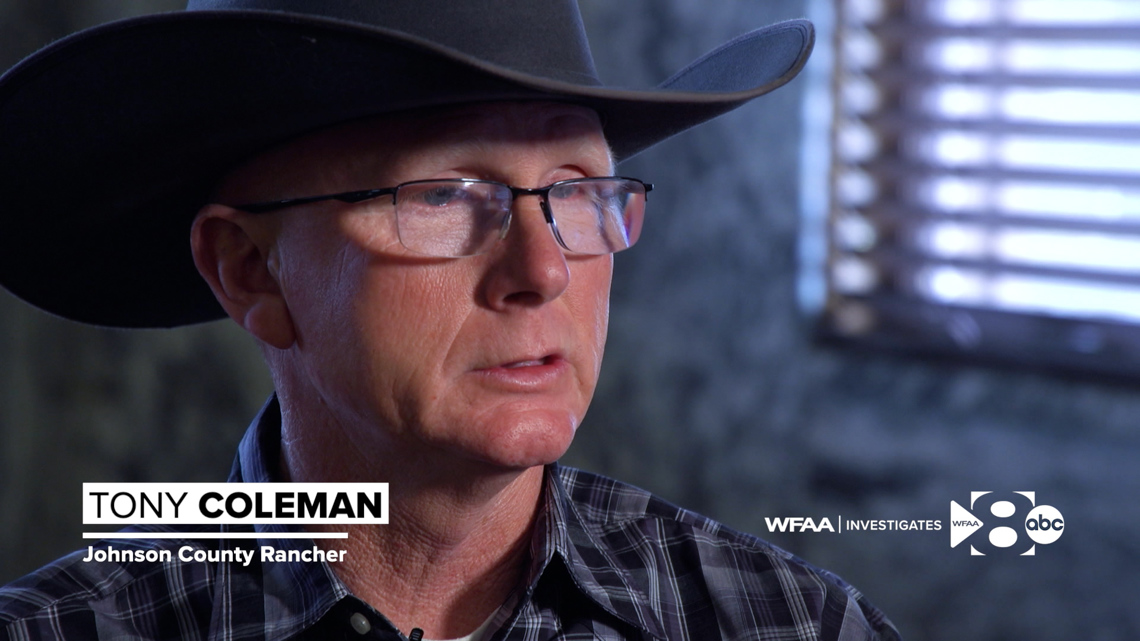

Rancher Tony Coleman’s cattle roam 300 acres just outside Grandview. He said what was found on his land has turned it toxic.

“We are nervous, and we are scared,” he told WFAA.

Coleman said his land is contaminated and his livestock and fish are dying because of the product his neighbor used to fertilize his crops.

“You have your whole livelihood taken from you,” Coleman said.

He said he’s had 10 cows, two horses and five ponds full of fish die.

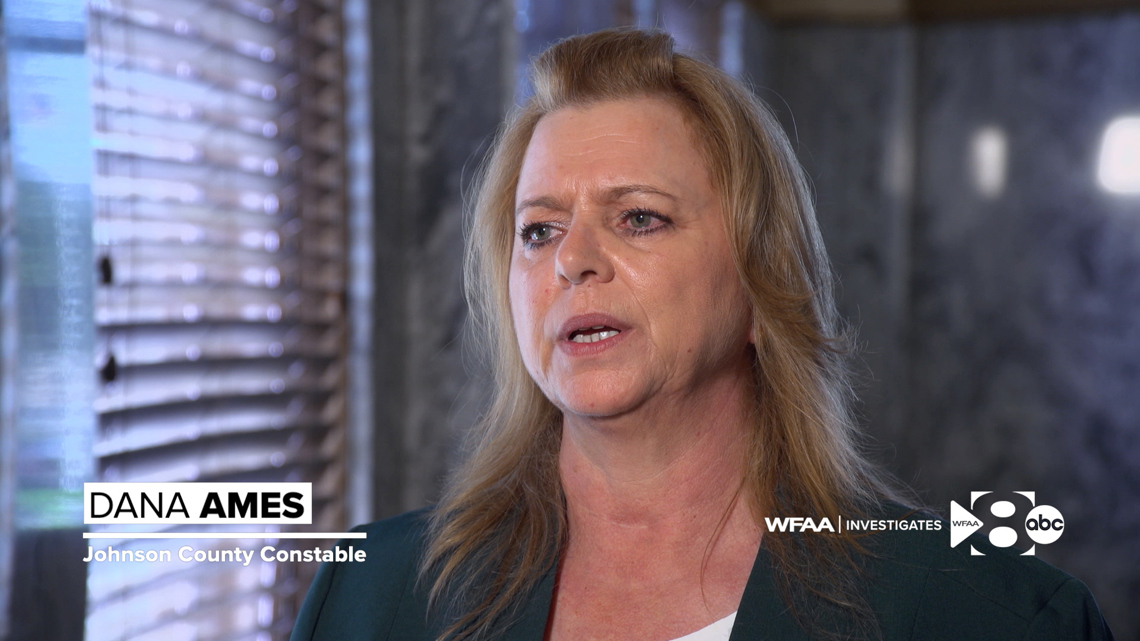

Late last year, he contacted Johnson County Constable Detective Dana Ames. She headed out to the ranch to check it out.

Ames said she found what she later learned were piles of fertilizer made from biosolids, which come from human waste and are full of what researchers call PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.”

“It’s chemicals that are manmade,” Ames said. “It’s in the sewage sludge. It’s in the biosolids.”

For a year, Detective Ames partnered with scientists and experts to try to figure out how toxic manmade chemicals ended up on ranchland in rural Texas.

She recently presented her findings to the Johnson County Commissioners Court.

“The contamination that has occurred on our victims’ properties is pervasive,” she told commissioners in her presentation.

This is what she and scientists with a group called Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility, or PEER, say happened. It all started at the facility used by the city of Fort Worth to treat its wastewater.

According to multiple studies and the Environmental Protection Agency, all humans consume PFAS chemicals, which are used to make all sorts of products including shampoo, carpet, frying pans and even makeup. The chemicals end up in our human waste, which is then sent to a wastewater treatment facility. During the treatment, biosolids are created.

Those biosolids, also called sewage sludge, can be used to make fertilizer, which is what a company called Synagro does.

And Synagro has a contract with the city of Fort Worth to use their biosolids to make fertilizer.

Tony Coleman and four other landowners are suing Synagro for the contamination on their land.

“It’s scary and I think our clients are hopeful there will be some relief for them,” said attorney Mary Whittle, “but they are looking at having to abandon their farms and potentially euthanize all their animals, which is extremely emotional and hard to face.”

In an emailed statement, Layne Baroldi, Synagro’s vice president of government affairs, told us that the company denies the allegations in the lawsuit, and said its fertilizer is safe.

“The biosolids applied by a farmer working with Synagro met all U.S. EPA and Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) requirements,” the statement reads. “U.S. EPA continues to support land application of biosolids as a valuable practice that recycles nutrients to farmland and has not suggested at this time that PFAS in biosolids requires any changes to current biosolids management practices.”

Biosolid fertilizer is sold across the nation for agricultural use. According to PEER, it sometimes contains toxic levels of PFAS.

The farmers who buy it “are led to believe this is safe and it’s cheap fertilizer and they have been victimized as much as anybody,” said Johnson County Commissioner Larry Wooley

Experts say PFAS chemicals are carcinogenic and can kill animals, fish, and humans.

Detective Ames said Eurofins Lancaster Laboratory tested the tissue of the cows, fish and horses that died on Coleman’s ranch. She said they found extremely high levels of PFAS in animal tissue. Tests also found it in the well water in Johnson County. Eurofins is a TCEQ state approved certified lab.

“The well water, all the animal tissues tested 100-percent contaminated,” Ames said. “We had 100 percent contamination on these properties.”

County Commissioners were shocked.

“My first thought was, you know, this is Chernobyl, a nuclear meltdown,” commissioner Kenny Howell said.

In 2022, the Maine Department of Environmental Protection banned the use of the biosolids fertilizer after farms were contaminated with high levels of PFAS and animals and fish died.

Here in Texas, the TCEQ regulates biosolids, and the Texas Feed & Fertilizer Control Service and Office of the Texas State Chemist have general authority concerning use of fertilizer products.

The TCEQ told WFAA that “biosolids that have met rigid requirements to prevent contamination from metals… and significantly reduce pathogens may be approved for land application.”

A spokeswoman for the Texas Feed & Fertilizer service at Texas A&M said someone from their office attended Ames’ presentation to the Johnson County commissioners court, but said they couldn’t comment because of the ongoing litigation.

Ames and the county commissioners say regulations don’t go far enough and that there is little to no follow up testing for PFAS chemicals once fertilizer is applied.

“This stuff should be banned all across America,” said rancher Tony Coleman. “I mean, what are our children going to do? You are ruining their land. You are ruining their water source… This has to stop.”

The EPA referred questions about the Johnson County case to state officials. The EPA is currently conducting a study on biosolids and possible contamination across the country and should have findings by December. It will determine what regulations if any will be imposed on companies that manufacture biosolids.

Ames and the scientists at PEER say the Texas Legislature and federal government have done little to regulate biosolids, but the EPA has started to ban or restrict the use of PFAS chemicals in everyday products.

“They are there for decades if not hundreds of years,” Ames said. “They will not go away. They will stay there and poison that land and water forever.”

More from WFAA Investigates: